|

|

| Festivals of the Maritime Koryak | 65 |

| The Whale Festival | 65 |

| The Putting-away of the Skin Boat for the Winter | 78 |

| The Launching of the Skin Boat | 79 |

| The Wearing of Masks | 79 |

| Festivals of the Reindeer Koryak | 86 |

| Ceremony on the Return of the Herd from Summer Pastures | 86 |

| The Fawn Festival | 87 |

| Other Festivals | 87 |

| Races | 87 |

| Festival of "Going around with the Drum" | 88 |

| Ceremonials Common to both Maritime and Reindeer Koryak | 88 |

| The Bear Festival | 88 |

| The Wolf Festival | 89 |

| Practices in Connection with Fox-Hunting | 90 |

| Sacrifices | 90 |

| Bloody Sacrifices | 92 |

| Bloodless Sacrifices | 97 |

V. — FESTIVALS AND SACRIFICES.

Festivals.

The cycle of festivals is different among the Maritime and the Reindeer Koryak, owing to the difference of their means of subsistence. A cult of the animals upon which their livelihood depends is developed among both groups; the Maritime Koryak worshipping sea-animals, while the Reindeer Koryak worship the reindeer herd. All the religious festivals of the Koryak centre around these animals.

Festivals of. the Maritime Koryak. — Following are the main festivals of the Maritime Koryak: the whale festival; the celebration at the putting-awav of the boat for the winter; and that at its launching in the summer. To the religious customs of the Maritime Koryak belongs also that of wearing masks.

The Whale Festival. — The whale festival is considered the most important one. It is called Yañya-ena'cixtitgin, which literally means "whale-service." Every killing of a whale is celebrated with a "whale-service;" but the main whale festival occurs in the fall, usually in October, after the capture of a whale. Since whales are very seldom obtained nowadays, the ceremony is celebrated in connection with the capture of a white whale.

In describing the fall festival of the Kamchadal, Krasheninnikoff calls it the festival "of expiation of sins." Judging from the description of the rites performed during this festival, it abounds in interesting details ; but, unfortunately, their inner meaning remained unknown to Krasheninnikoff. In one passage he states that the means of expiation of sins was confession. Women suffering from nervous fits confessed transgressions of various taboos committed by them, and were then comforted by one of the old men. Such a confession of transgressions of taboos constitutes the expiation from sins also among the Eskimo."

On the other hand, it may be seen from Krasheninnikoff's description, not only that this was a family festival, but that all inhabitants of a given village took part in it, even those not related to each other. 3 It signified

1 Krasheninnikoff, II, p. 125. 2 Boas, Baffin-Land Eskimo, p. 121.

3 In the description it is not mentioned in whose house the celebration took place; but Mr. Bogoias (Anthropologist, p. 606) interprets the description as meaning that there were special ceremonial houses mong the Kamchadal. Krasheninnikoff tells (II, p. 135) how the women of the house in which the festival was celebrated (apparently the winter house) walked off to the balagans (that is, the summer huts raised on posts), an how each returned into the house with sacrificial grass and provisions. The grass and provisions were received by two men appointed for that purpose. The grass was hung upon the charms; and the provisions, especially dried fish, were chopped with a hatchet, and returned to the woman from whom they had been taken, onli a small piece being thrown into the fire as a sacrifice. Each women also put some sacrificial grass upon the hearth. Then they passed from one corner to the other, treating each other with dried fish, as a symbol of a future abundance of food-supply.

[65]

9—JESUP NORTH PACIFIC EXPED., VOL. VI.

66

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

that the summer and fall hunting seasons were over, and was intended to influence the deity so that the hunt of the following year would also prove successful, and that the winter would pass without sickness, or visitation of the kalau. This is Steller's interpretation of this festival, to which he devotes only a few lines. Krasheninnikoff also describes how a grass whale filled with blubber and other kinds of provisions is made. It was tied to the back of one of the women, and at a certain moment those who participated in the celebration threw themselves upon it, tore it up, and ate it, apparently in imitation of a successful hunt.

Parry 1 tells, that, among the Central Eskimo, the capture of a whale is celebrated by a great festival. According to his brief description, the whale is hauled inside of a stone enclosure about five feet high. Several men flense it, and throw the pieces of meat over the stone wall. The crowd which stands on the other side catch the flying pieces; while the women, who are inside, sing, forming a circle, in the centre of which are the whale and the men who carve it.

The

killing of a whale was also celebrated by the Aleut with a feast,

with

beating of drums, dances, and masks. The dances had a mystic signifi-

cance.

Some of the men were dressed in their most showy attire; while

others

danced naked, wearing large wooden masks, which reached to their

shoulders,

and represented various sea-animals.2

Krasheninnikoff says that the Reindeer Koryak have

no festivals, and

adds,3 that the Maritime Koryak observe their festivals at the same

time as

the Kamchadal, but that they are as little capable of explaining the meaning

of their ceremonies as the Kamchadal. Unfortunately Krasheninnikoff does

not

offer any, not even a superficial, description of the festivals of the Maritime

Koryak,

which would be interesting for the purpose of comparing the rites of

a

previous period with those observed by me.

The essential part of the whale festival is based on the conception that the whale killed has come on a visit to the village; that it is staying for some time, during which it is treated with great respect; that it then returns to the sea to repeat its visit the following year; that it will induce its relatives to come along, telling them of the hospitable reception that has been accorded to it. According to the Koryak ideas, the whales, like all other animals, constitute one tribe, or rather family, of related individuals, who live in vil- lages, like the Koryak. They avenge the murder of one of their number, and are grateful for kindnesses that they may have received.

The

whale festival is not a family festival, but a communal one. All the

inhabitants

of the village participate in it; but the owner of the skin boat

by

whose crew the whale has been killed, acts as the host, and takes charge

of the festival. He invites his neighbors; and the celebration, which lasts a

few days,

takes place in his own house or in the largest one of the village.

1 Parry, II, p. 362. 2 Dall, p. 139. 3 Kvasheninnikoff, II, p. 217.

67

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

If several boats participated in the capture of the whale, the master of the festival is the one who dealt the deadly blow with his harpoon.

The

villages of the Maritime Koryak, especially their summer villages,

are

mostly situated on rocky shores rising to some height above the sea'.

From

the roofs of the houses a wide view of the sea may be had. When

the

inhabitants of the village are out sealing, the women frequently go out

and

sit on the roof to await the return of the boats. When the women

of

a certain house discover

their boats

towing a

whale, they put on their embroidered dancing-coats, trousers,

and shoes, and masks of sedge-grass,

take sacrificial alder-branches and fire-

brands from the

hearth, and go to

|

|

the beach to meet the whale. (The Koryak custom of bringing out fire-brands from the hearth to meet the newly married daughter-in-law or son-in-law is regarded as a sign that they now belong to the family hearth. In ancient times welcome and honored guests were in the same way received with fire- brands from the hearth.) If there is an old man who staid at home in the house, he also puts on a dancing-costume, a grass collar, and a grass girdle, ties plaited grass all over his dress, and takes a whip-like wand of plaited sedge-grass, which he brandishes, apparently to chase away evil spirits. The women and the old man are joined by women from other houses, also attired

68

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

in their festive coats; and all welcome the whale, dancing around the fire that is brought from the hearth, and is built up outside the house.

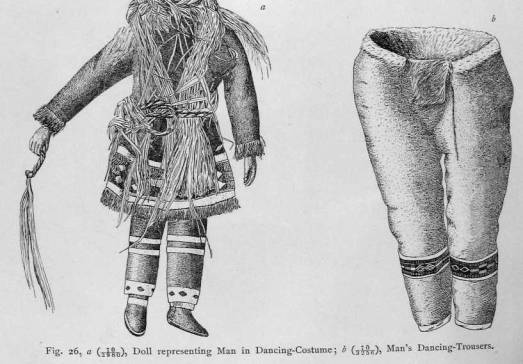

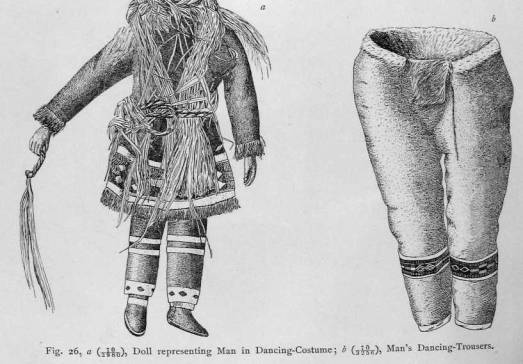

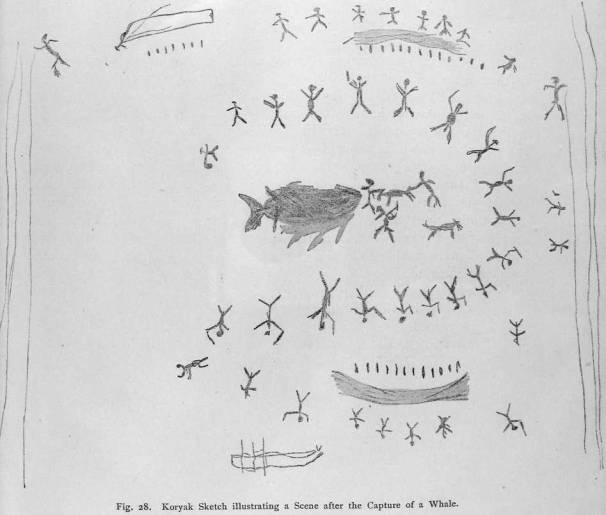

A man's embroidered dancing-coat is represented on Plate I, Fig. 2 (opp. p.48). Other parts of dancing-costumes are shown in Figs. 26 and 27. Fig. 26, a shows a doll made by the Koryak Lalu' from the village of Kamenskoye, and represents an old man dressed in a dancing-costume, and tied around with sacrificial grass; while Fig. 28, a reproduction of a drawing by the old Koryak Yulta of the village Kamenskoye, represents a scene after the capture

|

|

| Fig.27, a (70/3599), Woman's Dancing- Coat; b (70/3257 a), Woman's Dancing- Boot. | |

of a whale. In the middle, the whale is lying on grass, one side carved. On the right side of the whale a dog is being sacrificed. Two men are holding it, — one by the head, the other by the hind part, — and a third is holding a spear, ready to stab it. On the ground, near this group, is a dog already slaughtered. Around this central group, men with knives in their hands, and women, are dancing, forming almost a complete circle. On the upper and lower parts of the illustration four places are shown at which grass is spread. Usually the straw-like stems of Elymus mollis are used for this purpose. Slices of whale-meat, represented by a number of vertical lines, are spread on the grass; and people are standing near them. At the sides of the figure the owners of the skin boat are seen spreading out the harpoon-lines which were used in the capture of the whale, and which must be dried.

69

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

As I said before, the

whale festival is at present celebrated in connection with

white-whale hunting, for large whales are nowadays very rare in the bays of the

Okhotsk Sea. I will describe here the celebration of a festival that I witnessed in the village of Kuel.

It was on the nth of October, 1900. A

white whale had been caught the nets which the Koryak Qaivi'lok had set for

catching seals. In some

places the ground was covered with

snow. Blocks of ice had begun to accumulate on the beach, every retreating tide adding to the accumulation

of slippery

salt-water ice. Early in the morning several men started out on a sledge to fetch the white whale.

When they were returning to the village, bringing

the whale,

a few

women in

dancing-costumes, but

without masks,

70

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

came out to welcome it with burning fire-brands. They put these down on the ground at the point where it began to slope toward the shore, together with a dish filled with berries of Empetrum nigrum and covered with sacrificial sedge- grass. As a strong wind was blowing, stones were put upon the grass to prevent its being blown away. The women danced, shaking their heads, moving their shoulders, and swinging their entire bodies with arms outstretched, now squatting, now rising and singing, "Ah! a guest has come!" and exclaiming joyfully, "Ala la, la, ho, ala, la, la, ho!" In spite of the cold and wind, they were covered with perspiration, owing to their strenuous and violent movements; and they soon became hoarse from singing and screaming. From time to time, one or the other remained squatting for a little while to take a rest, and then again rejoined the dance (Plate IV, Fig. I). When the sledge with the whale had reached the shore, the women went into the house, took off their dancing-costumes, and soon returned with pails and troughs for gathering the blood and the entrails, and with bunches of grass on which to spread the meat and skin before they should be divided. The men threw the whale from the sledge upon the ground. One of the women, among whom were the two wives and two sisters of the owner of the nets that had caught the whale, took alder-branches and a bunch of sacrificial grass, and, after having whispered an incantation, put them into the mouth of the white whale. There is no doubt that this was a sacrifice symbolizing a meal given to the whale; but the Koryak were unable to explain to me the meaning of the alder-branches. "Our forefathers used to do this way," they said. Then the women cleaned the body of the whale with grass, and covered its head with a hood plaited of grass, apparently with the idea that the whale should not see how it was going to be carved.

Before putting the branches into the whale's mouth, Kïlu'-keña,1 the older widowed sister of Oaivi'lok, known in the village as the woman most expert in pronouncing incantations, bent over the whale's head, and, assisted by her younger sister, pronounced the following incantation : 2 —

"The Creator said, 'I shall go get a white whale for my children as food.' He went and got it. Then he said, 'I shall go for an alder-branch.' He went and brought a branch. He brought the branch for the whale. Later on he again procured the same white whale: again he brought a branch. Thus he always did, and thus he always hunted."

Then the men flensed the whale, and the women gathered the blood, and divided the meat, blubber, and skin into parts (Plate IV, Fig. 2). At the same time that the white whale was brought, other hunters from the settlement brought a ringed seal (Phoca hispidá) and a thong seal (Erygnathus barbatus); and these were included in the following festive ceremonies. They were also

1 She is represented with a drum on Plate III.

2 I lerned the meaning of this incantation many months after, when I revisited the settlement in the spring. Unfortunately the text of this incantation remains undeciphered. I therefore give only the translation.

вставить рисунок!!! 71

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

cut up in front of the

village. The head of the white whale, as well as the heads of the two seals,

were wrapped up in grass hoods, and put upon the roofs of the storehouses.

Next the inhabitants of the village made preparations for the festival. During the day a dog was slaughtered at the seashore as a sacrifice to the master of the sea. It looked as if the entire village had moved over to Qaivi'lok's house, the owner of the net in which the white whale was caught. The women spent all their time there, working. They plaited travelling-bags of grass for the white whale, made grass masks, prepared berries and roots etc. By chance only one guest from a neighboring village was present at this festival, while it is customary for many visitors to come to participate in the whale festival. The communal character of this festival was also due to the fact that all the families belonging to the village set up their nets together, and that the flesh of the sea-animals was divided among them. Only the head and skin of the animals belonged to the man in whose nets they had been caught. But, although the white whale's skin was not divided, all parti-

|

cipated when it was eaten in Oaivi'lok's house. Many of the men

and women spent all the time during the celebration in eating in Oaivi'lok's house,

and even slept there. In the evening of the same day, Oct. 11, the first reception in honor of the guests (the white whale and the seals) took place. When I entered Oaivi'lok's house, accompanied by my wife and Mr. Axelrod, it was full of people (Fig. 29). The skin-covered sleeping-tents and the bedding had been taken out of the house. All around the house, in the spaces between the posts and the walls, the women were busy cooking, cutting up blubber, grinding and mixing spawn and berries, and cutting edible grasses and roots. The men were sitting in a half-circle near the posts, while the youths were standing or sitting on the ground, near the hearth. The space to the left of the entrance, as far as the first middle |

|

| Fig. 29 Plan of Underground Houses, illustrating the First Part of the Whale Festival. a, The Shrine; b, Lamps and woman cooking; c, Men sitting; d, Children; e, Place in which the writer and his companions were seated; f, Fireplace; p, Posts; v, Porch. |

post, was unoccupied. In

this section, near the wall, was the shrine (op-yan) in

which were

placed the charms, attired in grass neckties, - the sacred fire-board,

the master of the nets, the house-guardian (yaya'kamaklo), the spear

consecrated to the spirit of the wolf, and a few other minor guardians Among

them was a wooden image of a white whale (Fig.

30, a), in front of

72

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

which was a small cup filled with water (Fig. 30, 6), which was changed every day during the festival; and on a grass bag were small boiled pieces of the nostrils, lips, flippers, and tail of the white whale. The little cup is called e'naxla-ko'iñin ("for a friend a cup"). A similar cup, used in the whale festival, is represented in Fig. 30, c. The sacrificial parts are called tayñinya'ñvo

|

|

("desired [pieces]"); that is,the choicest. It is interest-ing to note that the sacrificeto the spirit of the animalconsists of parts of its ownbody, while, on the otherhand, these parts representthe white whale itself. It was very quiet in the house. The people spoke in whispers, and the host pointed out a place for us in front of the shrine. We sat down on the log which separates the sleeping-place from the middle of the house. The interior of the house had a strange, mysterious, and at the same time |

|

Fig. 30, a (70/2992), b (70/2856), c (70/292906) Wooden Image of a Whale, and Sacrifical Cups used at the Whale Festival. Length? 21 cm., 17 cm., 8.5 cm. |

a depressing look. There was no fire on the hearth; the coals were only smouldering. Eight stone lamps on wooden stands, the number corresponding to the number of families that participated in the festival, were burning with smoking flames all around the house, where the walls are slanting, and gave off a very unpleasant smell of seal-oil. Their light was lost in the darkness of the vast underground house, the largest in the village. The walls, black from soot, completely absorbed the light of the lamps, and it was very difficult to discern the figures of the women, who were busy cooking. The men and the children were sitting motionless in the middle of the house. All were silent, or spoke in whispers, for fear of awaking the guest before it was time.

At last the preparatory cooking was done, and all went outside, since, during the ceremonies of that evening, no one was allowed to leave the house. Soon all returned, and each family brought a bundle of fagots, and they built a large fire on the hearth, which lighted the house, and made it appear less gloomy than before. Amid the silence that was still reigning, the women placed near the fire kettles brought from their homes, and melted in them the blubber of the white whale and seals. The women continued to whisper one to another. After the oil was tried out, they went back, each to her

73

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

lamp, and mixed the oil with the cut willow-herb [Epìlobium

angustifolium). These were

ground with spawn of the dog-salmon {Oncorhynchus keta), various kinds

of berries, — crow-berries (Empetrum nigrunì), cranberries [Vaccinium

vitis idaa L.), blea-berries (Vaccinium

uliginosuvì), and cloud-berries [Rubus chamczmorus), — and roots of Claytonia

acutifolia, Hedisarum obscurum, and Polygonum viviparìim.

A little water was added, and the whole was kneaded in troughs, for making

puddings, which the white whale was to take alono-on its journey. These

puddings are called ci'lqacil. When they were ready, the women representing

the different families passed from one corner to the other, and exchanged

presents, consisting of small pieces of pudding. After this exchange of presents,

the host and other men brought in from the porch the heads of the white

whale and the two seals, and hung them on a cross-beam at one side of

the hearth.

The silence was suddenly interrupted. From all sides of the house were heard joyous

exclamations of the women, who exchanged greetings with one another, — "Here dear

guests have come!" "Visit us often;" "When you go back to

sea, tell your friends to call on us also, we will prepare just as nice food for them as for you-,"

"We always have plenty of berries;" etc., — and they pointed with their

fingers at the puddings that were placed on boards. The fire of the hearth

was supposed to represent the sea, to which the whale returns. The charms

which guard the whale's skin, as described above, are not used in the equipment

for the home journey of the white whale.

Everybody in the house was carried away with excitement.

The men and children talked aloud, and crowded around the hearth.

Soon the hunters hung up over the hearth, to boil, the livers of the white whale and of the

seals, and the skin of the whale.

Then the host, a grass collar around his neck, took a piece of the fat of

the white whale, and threw it into the fire, saying, "Caqhicnm" [Being,

Something-existing], "we are

burning it in the fire for thee!"

Then he went to the shrine, placed pieces of fat before the

guardians, and smeared their mouths with fat.

Thereupon all those present in the house began to partake of the food.

They ate dried fish (dipping it in white-whale or seal oil), boiled seal-meat and

whale-meat, broiled skin of the white whale, and pudding.

The naked bodies of the

men (who had taken off their coats), the excited faces of the women, the

children's faces smeared with oil, the smoke of the hearth, and the soot from the lamps, — all

these together offered a strange sight.

The concluding ceremony

of the evening was divining with a shoulder-blade of a seal. This was done by two old men. One held the shoulder-blade, and the other one piled burning

coals on it. All

the men examined the cracks which formed in the

shoulder-blade. First

a crack appeared parallel to the longer side of the

bone, which caused anxiety among those present.

Such a crack indicates dry

and and mountains.

Since the object of the divination was to discover

whether the white

whale would go back to the sea and call others

10—JESUP NORTH PACIFIC EXPED., VOL. VI.

74

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

to visit the settlement, the augury desired was a

line indicating the sea. To

the

delight of all the participants in the ceremony, there soon appeared another

crack across the bone,

and intersecting the

first line. Such

a line indicates the

sea; that is, that the home journey of the whale

will

be happily accomplished (see Fig. 31).

|

The

ceremony of the equipment for the home

journey of the white whale took place on the

fifth

day, in the morning of the 15th of

October. During

the three days intervening, — from

the nth to the

15th, — the inhabitants did not do

any work. They

called on each other, and gave feasts;

but most of their time was spent in the house in

which the

ceremonies were taking place. The old

men ate fly-agaric, and, when the intoxication had

passed, thtey told whither the "Fly-Agaric Men"

(Wapa'qala'nu)

had taken them, and what they had seen.

Thewomen and the young people sang and

beat the drum.

In the evening of the 14th there was another gathering in Qaivi'lok's house. This time only two lamps were burning in the house. The women finished plaiting the grass bags required for the ceremony, and the host beat the drum and sang. Then his sisters beat two |

| Fig.31 Shoulder- Blade of a Seal, used for Divination. (From a sketch.) | |

drums, and sang in praise of the guests, — that is, of the white whale and the seals, — dancing at the same time in the same way as they had done on the shore when meeting the white whale. During this ceremony they were overcome with such a frenzy, that the deafening roar of their drums was completely drowned by their desperate shrieks, which alternated with guttural rattlings.

On Oct. 15 the frost was rather severe, the minimum temperature being —23°C. For more than a mile the shallow beach was covered with blocks of ice, so that the high tide no longer reached the village. Winter had set in, and all hunting of sea-animals ceased.

By ten o'clock in the morning I was called into Qaivi'lok's house. The low entrance-door leading from the porch, which is closed for the winter, was still open. So far the opening in the roof had served only to admit light from out- side, and to let out the smoke from within, but not as an entrance. The hearth was turned into something like an altar. On it were lying the travelling-bags plaited of grass (Elymus mollis), and filled with puddings which had been frozen outside. The heads of the white whale and of the seals had been placed on the altar, and sacrificial sedge-grass was hung around them. It was a bright, sunny day; and the light passing through the smoke-hole illuminated well the centre of the house and the hearth, leaving the recesses nearer the walls in semi- darkness. The light in the middle of the house permitted me to take a photograph of the hearth without the use of the flash-light (Plate v, Fig. 1).

Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI. Plate IV.

Fig. i. Welcoming the Whale.

Fig 2. Flensing the Whale.

The Koryak.

Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI. Plate V.

Fig. 1. Equipping, the Whale for the Home Journey.

Fig. 2. Mask Dance.

The Kopyak.

75

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

Both sisters of the

owner of the house — Navaqu't (the chief's wife), and Kilu'kena (who was

known in the settlement for her skill in incantations) — put on grass masks (Fig. 32). They knelt down before the hearth,

bent their heads

|

over the altar so

that their masks covered the bags, and pronounced an incantation. Not far from the hearth their

brother was standing. He wore a

grass collar, but no mask. Being a man with a "strong

heart," he was not afraid to meet with

face uncovered the spirit of the white whale, which is supposed to be

present at the ceremony of the equipment for its home

journey; but the women, not being sure of their presence of mind, wore

masks.1 Before the kneeling women, on a separate

plate, was a small sacrificial pudding covered with sacrificial

grass, for the spirit of the white whale. When the incantation was

finished, the women arose and

took off their masks; and their brother took the plate

with the pudding, and examined it carefully, assisted by the old men. After

a long search, they discovered some slight scratches in two places on its smooth

surface, and felt per-fectly satisfied, taking them for

traces left by the spirit, who apparently had received the sacrifice with

favor. This indicated that the white whale was going back to sea ot fulfil its

mission. The

unwilling- ness of the white

whale to return to the sea would be a foreboding of hunger and other calamities.

In Tale 20 it is related that Big-Raven's and Miti s fathers, unable to

send home the whale, were so frightened on account of the consequences of such

an event, that they ran away, no one knows where, deserting their houses,

and leaving their small children uncared for. |

|

|

Fig.32 Grass Mask |

1 It is an interesting fact that the custom among the Yukaghir of wearing leather masks when dissecting the corpses of their dead shamans was explained to me in the same manner. People do not dare to look with uncovered faces at the body of the shaman. We find the same idea among the Aleutians. They believed, that, while the mystic rites of the annual festival in December were going on, a spirit or power descended into the figure which was prepared for the festival. To look at or see him was death or misfortune; hence the Aleutians wore large masks carved from driftwood, with holes cut so that nothing before them or above them could be seen, but only the ground near their feet. A further illustration of the same idea was shown in their practice f putting a similar mask over the face of a dead person when the body was laid in some rock-shelter. The departed one was supposed to be gone on his journey to the land of spirits; and for his protection against their glances he was supplied with a mask (Dall, p. 137).

76

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

After the favorable reception of the sacrifices by the white whale, the people proceeded to send it home. Two men went out, ascended the roof, and let down into the house long thongs, to which the travelling-bags (Fig. 33) and the heads of the white whale and the seals were tied. Before pulling them up, a preliminary test of lifting them had been made, and it turned out that they were very light. This was the last divination before the final eguipment for the home journey of the white whale and the seals. For three

Fig. 33 Grass Bag for Whale Festival. Length, 120 cm.

days the bags of provisions remained on the roof.

Then the puddings were

eaten,

and the grass bags and masks hung up in the small storehouse. I

acquired

the latter subsequently for my collection (see Figs. 32, 33). Toward

spring

they are usually carried away into the wilderness, where they are left

on

the ground, or hung from the branches of a tree. It is forbidden to

burn

them.

The

following facts are of interest in connection with the festival for

"equipping

the whale for its home journey." The tendency of "having nothing

in

common" with the hearth of somebody else is not as strong among the

Koryak

as among the Chukchee. The family hearth of the Chukchee is

sacred,

and the fire of one family must not be brought in contact with the fire

of

another family. The kettle or teapot of one house must not be brought

near

the fire of another family, not even into another house. It would desecrate

and

infect the family hearth. Among the Koryak the taboo of "non-com-

munion" with a stranger's hearth is observed in a lesser number of cases.

For

instance, among

the Maritime

Koryak the

taboo of carrying fire from

77

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

one house to another is observed only in summer, since

otherwise success in sealing may be brought to an

end. But during the whale festival, families that are not interrelated bring

into the house where the celebration takes place wood, dishes, food, and sacrificial grass. They build a fire

jointly, and cook together. On the other hand, before

the celebration takes place, all the bedding and the skin covers of the

sleeping-rooms are taken out of the house. Temporarily the house is thus transformed into

a ceremonial house.

In connection with this it may be mentioned, that,

during the Koryak fair on the Palpal Mountains,

which I visited, the Reindeer Koryak built a common oblong reindeer-skin tent. Each family covered a

part of the tent with their own reindeer-skins.

The house formed a long passage, on both sides of which the sleeping-rooms of the separate families were

put up. In two places, near the foci of the oval,

two hearths were built for general use. The Chukchee families that were present at the fair each put up a

separate tent.

Not all the Maritime Koryak have transferred the

ceremonies connected with the whale festival

to white-whale hunting, as it is done in the villages of Paren, Kuel, and Itkana. The Koryak of

Kamenskoye and Talovka told me that they celebrate

the equipment of the white whale for the home journey without any particular

ceremonies, right on the seashore, the customs being the same as those in practice after the capture of

seals. They cut off the head of the captured white whale or seal, put berries in

its mouth to feed it, hang sacrificial grass around it, and, turning its face

seaward, pat it, and say, —

| "I'nnaa | a'tci | vo'ten | aya'yan | I'miñ | qaitumgiya'nvo | hewñava'ta: | millalai'- |

kmemik." |

| "Soon | to-day | with (this) | tide (come). | All | relatives | induce: | come |

on." |

That is, "When the next high tide comes,

induce all your relatives to come with you to visit

us."

Then they add, "Go around the flippers of

those who do not wish to come."1

Thereupon they turn the face toward the village, and exclaim, "Uph, (he)

has come!" (Gik,

y'etti!)

The Koryak think that this incantation has the

effect of bringing sea-animals with the

following tide. Before sending off the head, they cut off a piece of the white whale's or the seal's liver-,

and the Koryak maintain that the liver of the next

animal caught will lack a piece at the same place.

The Reindeer Koryak from the Taigonos Peninsula,

a number of whom carry on sea-hunting

on a small scale during the summer, after having procured a white whale, offer a sacrifice of a reindeer or

a dog to the master of the sea (añqa'ken-eti'nvila'n).

They cut off a piece of fat from the white whale or seal, and, throwing it into the fire, they say,

"Come back later on.

1

The Koryak words represented by this last sentence could not be literally translated.

78

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

The Putting-away of the Skin Boat for the Winter. — Soon after the whale festival, the Maritime Koryak celebrate the festival of putting away the skin boat. This is called Mena'tva'ñtara, which literally means, "Let us pull ashore the skin boat." While the whale festival is celebrated by the entire village, this is a family festival. Every family puts away for the winter its own skin boat. Guests are not invited for that event, and no special food is prepared. This festival is celebrated at the first new moon following the close of the hunting-season. First of all, the covering of seal-skins is taken off the wooden frame of the boat, on the beach. Then the fire in the house is put out. The ashes and all refuse on the hearth are picked up, carried out, and thrown at the foot of one of the guardians of the habitation standing in the settle- ment, preferably near the one belonging to the family which puts away its boat. It is supposed that by putting out the old fire, and removing the ashes and refuse, all hostile spirits are also removed from the house. Then a new fire is started outside, near the boat, by means of a drill and the sacred fire-board. After a flame has been obtained, a fire is built of alder-branches; and pieces of seal and white-whale fat are thrown into it as a sacrificial offering. During the ceremony the mouth of the sacred fire-board is smeared with fat, its eyes are cleaned with a knife, and they say to it, "Behold! the sea now frozen!" (Oihite'hin a'ñqan geqi'talin!)

When the fire outside has gone out, the frame of the boat is put away on the snow behind the houses. Then the people enter the house and start a new fire inside. In olden times the fire was brought from outside; but at present it is started with a strike-a-light or a match. In those settlements that are nearer to Kamchatka, and which have become more or less Rus- sianized, the drilling of fire on the sacred fire-board is observed as a mere matter of form. The people merely insert the drill with the bow into the little hole of the sacred fire-board; but the fire is really started with a match.

After the new fire has been built on the hearth, the outer entrance-door of the porch is boarded up, covered with earth and snow, and a ladder is put into the smoke-hole. During the summer this ladder is kept on the roof. Its top, which has a carved face, and its foot, are smeared with fat, and charmed by means of an incantation, in order that the ladder may not admit any kalau into the house. The placing of the ladder and the closing of the porch-door take place in those settlements that are inhabited all the year round, as, for instance, in the village of Kuel. In settlements that serve only as winter residences, like Paren, the ladder is not taken out for the summer, and the outer door is never opened.

After

the dwelling has been arranged for the winter, a ceremony is per-

formed

symbolizing the departure of the boat on a journey out to sea. Forked

alder-branches

are put on the frame of the boat at the places where the

oarsmen

sit, and also on the stern, while a bundle of sacrificial grass is hung

Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI. Plate VI.

Ceremony of starting the New Fire.

The Koryak

Jesup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI. Plats VII.

Fig. i. Boat-Frame, with Sacrificial Grass attached.

Fig. 2.

Sacrifice of a

D0g

The Koryak

79

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

on the prow. Shaking the grass, the people say, "Well, start off!"

Then they

enter the house, dress up the sacred fire-board in a toy coat, put around its neck a thong with

a harpoon, give it a knife, and carry it outside. The owner of the house says

to it, "Now, go to the boat!" (Toq! Astve'ti qatai'!) Then somebody in the house coughs, as though replying to some one, and says, "Aha! father

has returned." The sacred fire-board is then taken'back into the house and put

away to rest until the following spring. I was unable to find out the

significance of this symbolic departure of the boat-frame and sacred fire-board, and

the return of the latter into the house. It may be surmised that the

spirit of the boat and of the sacred fire-board depart for the sea to stay there for the winter.

In the village of Kuel, the ceremonies of sending the boat out to sea, and the starting of a new fire,

take place independently of each other. The boat is sent to sea immediately

after the close of the hunting-season. From the time when the skins are taken

off from the boat until the moment when the frame with the sacrificial grass, and the

alder-branches as its oarsmen, is placed on the snow, no fire is

allowed to burn in the house. The frame of the boat remains on the

snow throughout the winter (see Plate Fig.

i).

In Kuel a new fire is procured from

the sacred fire-board after the first new moon of winter.

The old fire on the hearth is again put out, and then the new fire

is started in the house.

Three men without coats, half naked, participate in this performance.

One holds the sacred fire-board; another, the upper support of the drill; while the third

one works with the drill-bow (Plate vi).

The Launching of the Skin Boat. — The spring festival of launching the boat is called "Mena/ tineyevune," which means literally, "Let us launch the boat," and is also a family festival. The seal-skin cover of the boat is soaked in water and put on the boat-frame, which is placed bottom up. The edges of the cover are turned inside, and tied with straps to the frame. Then a sacrificial fire is obtained from the sacred fire-board, and is kept burning under the upturned boat. Pieces of seal-fat are thrown into the fire as a sacrifice to the boat, and the mouth of the sacred fire-board is smeared with fat. Then its eyes are cleaned with a knife, and they say to it, "Well, your eyes have become clear, the sea is open, look out." (Ga, lela't eciha'tbe, a'ñqan gava'ñtalin, qihite'hin !) The fire under the boat is allowed to die out, and the upturned boat is left to dry. Then it is launched.

The Wearing of Masks. — Heretofore it was not known that the Koryak wore masks in connection with their religious ceremonies. Not one of the former travellers makes mention of them.1 I referred above to the use of

1 There are no indications, either in Krasheninnikoff's or in Steller's descriptions of the Kamchadall, that they wore any wooden or grass masks, although Krasheninnikoff does mention that during the fall festival of "purification from sins" those participating in it used to adorn themselves with sacrificial grass, out of which they made wreaths, necklaces, and belts.

80

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

grass masks by the

Maritime Koryak

during the whale festival.

I also found wooden masks

in use

among them. In

October, 1900,

I sent

Mr. Axelrod from the

village of

Kuel to

the winter village of Paren for the purpose of taking anthropometric

measurements of the

inhabitants who had just moved there

from their

summer settlement. Mr.

Axelrod, on

his return, brought back,

among other things, a few wooden masks.

Since those masks appeared to

me to be similar to the crude masks of the northern Alaskan Eskimo, and since the use

of masks in general

suggested a possible contact between the Koryak and the tribes

of the western coasts of America, I went personally to the village

of Paren in order to acquire more detailed information regardingthe meaning and use of these masks.

The settlement of Paren is fifteen miles distant from

Kuel. It

is situated on the left bank of the Paren River, ten miles above

its estuary. The

inhabitants spend spring, summer, and

autumn on the seashore

in the settlement of

Khai'mchik, at the mouth of the river Paren. As

soon as

the hunting-season closes, they

move to Paren. While

the seashore is

altogether treeless, forests

grow near the winter

settlement, offering

some protection

against sea gales, and furnishing

wood for fuel and building-material

In Paren I learned the following about the use of masks, called by the Koryak ulya'utkoucñin (literally, "wearing of masks;" from u'lya, "a mask"). They are worn during the first winter month after the new moon. Their use is

partly for religious purposes, partly for amusement, the celebration being a kind of masquerade. The object of

walking about in masks and masquerade costumes is to drive away the kalau (kne'ñvit-aita'tì)1

who have taken pos- session of the houses during the

absence of the people in summer. The masks represent Big-Raven and members of

his family, who constantly waged war with the kalau. However, when the

masked performers descended into the house where I stopped, they were met with

shouts of "Ugh! kalau have arrived!" (Gik, ñe'nveticñin yelxi'vi!)

which was apparently meant either as a joke, or to frighten the kalau that were in the

house. There are masks representing men and others representing women. The

difference between them is that the former have mustaches, in a few cases also

chin-beards, drawn with black paint or a piece of coal, while the latter are

not painted at all. In Paren, only young men wore masks, not girls. They

were dressed in the most homely manner. They had pulled the sleeves of

their shaggy reindeer coats over their legs, and tied them so that the hood

dangled behind like a tail; and they wore old greasy leather shirts. They

rolled down into the house with great noise, missing several steps of the

ladder. They examined all the nooks and corners. Then they commenced a dance,

and represented various scenes of the coming winter life, — bear-hunting, sledge-riding, and

racing. Plate v, Fig. 2 (see opp. p. 74), represents three masked persons pretending to warm themselves by

a wood-

1 See p. 27.

81

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

pile. They received presents of pieces of sugar, tobacco, and ornaments, from the owner of the house. Thus they visited all the houses of the settlement.

Paren is the only village the entire western coast of Penshina Bay in which wooden

masks are used. The rest of the settlements are occupied

in summer as well as in winter; and the

wearing of masks is considered a sin. In Kuel, for instance, the Koryak refused to arrange

a "wearing of masks," as I reauested since it is forbidden. I was

told in Paren that the custom of "wearing masks" is still

observed in the settlements of Reki'nniki (Reki'nnok) and Podkaghirnoye (Pitka'hen),

along the eastern coast of Penshina Bay. Sub-seguently

Mr. Bogoras sent me a few masks from Reki'nniki. Besides, he found wooden masks among the Alutora Koryak of Baron

Korff Bay. Even the small

Fig. 4 Wooden Masks from Alutor Bay.

Reindeer

camps of the Alutora Koryak, which are inhabited by families some of whose

members live Maritime villages, also have

such masks and masguerades. It is noteworthy tha the inhabitants of these villages stay there during

summer also. According to

Bogoras,

the "wearing of masks" in these villages israther a masquerade.

The masks,

unlike those from Paren, have pendants attached, consisting of rings,

.tle bells, and other ornaments, or of models ofthings the masqueraders would like to receive.

To one of them ( Fig. 34, a) are appended

I I- JESUP NORTH PACIFIC EXPED., VOL. VI.

82

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

carvings representing a dog, a knife, and a ring. In the eastern settlements, both boys and girls wear masks. The masks of the Alutor Koryak have names. Mr. Bogoras has recorded two names : one, that of a woman's mask, --- Kïlu' (the name of Big-Raven's niece); and the other, that of a man's mask, — Amka'vvi. When the masks which represent Big-Raven's children enter a house, they dance, and enact various pantomimic scenes, but do not utter a word, and do not ask for anything; but the pendants on their masks indicate the kind of presents they would like to receive. These pendants very often call for things which, according to local prices, are considered very- valuable. These presents are never refused ; but later on the donors go into the houses of the masqueraders to get return-presents.

In North America the use of masks by Eskimo and Indians for religious or festive purposes, or for pantomimes, is not confined to the western slope of the Rocky Mountains; masks are found also among the Iroquois, the Pueblo tribes, the prehistoric inhabitants of Florida and we know that the Eskimo of Baffin Land use leather masks during festivals.1

Among the other Eskimo, only the Alaskan tribes use masks. They are also found among the Aleut. From the fact that among the Alaskan Eskimo, masks become more numerous and more elaborate the nearer we approach that part of Alaska inhabited by the Indians of Tlingit stock, Murdoch infers that the former might have borrowed masks of the Indians.2 I do not under- take to settle this question; but in simplicity and crudeness of finish, the wooden masks of the Koryak are so much like the Eskimo masks of Point Barrow, that it might be supposed that the Koryak and Eskimo masks origin-ated from a common source. It is very strange, however, that the Chukchee, who live between the Koryak and the Eskimo, have no masks.3

The collection of Koryak wooden masks in the American Museum in New York consists of nine specimens collected by me at Paren, two from Reki'nniki, and two from Baron Korff Bay, obtained by Mr. Bogoras. All the marks an made so that the eyes and month fit the face of the weaver. Fig. 35 represents the masks from Paren. All these masks are very rudely made. Only one of them (Fig. 35, f) is finished off somewhat smoothly. The outer edges of all the others are not smooth, but show the marks of the adze. Judging from its size, the mask shown in Fig. 35, f, was made for a child. It has no openings for the mouth and eyes. The eyebrows are drawn with black paint. The nose, though not short, is cut off straight at its lower end,

1 Boas, Baffin-Land Eskimo, p. 141.

The Yukaghir used to wear leather masks when dissecting their

dead shamans (see Jochelson, Yukaghir Materials, p.

110).

2

Murdoch,

p. 370.

3

Besides

the Koryak

and the

Yukaghir, whose

culture leans

toward that of American tribes,

and the

Siberian Buddhists,

some other

tribes of northern

Asia seem to use masks.

Potanin (II, p. 54) mentions that

the shamans

of the

Tchern-Tatars (Altaians) sometimes use masks (koro) made of birch-bark, and

ornamented

with

squirrels' tails to represent eyebrows and mustache.

83

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

thus representing the characteristic form of the Koryak nose. The groove between the lips apparently represents the teeth, two lines on the cheeks represent tattooing. The eyes are straight, and not narrow. Fig. 35, d,

Fig. 35 Masks from Paren (e, inner side).

represents a mask of a similar character. The masks shown in Fig. 35. a-c, have small openings for the eyes and mouth. Eyebrows, upper lip, and chin are painted with coal. The one shown in Fig. 35, c, has a cross on the

84

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

forehead. On the rim, on a level with the eyes, small holes are made for the straps by means of which the masks are tied on. The inner side of the masks is either flat or hollowed out very little (Fig. 35, e): thus the mask does not closely envelop the face, and the wearer is able to see the floor on either side. As stated before, the mask shown in Fig. 35, f, is finished more carefully, and at the back of it is a depression for the nose.

The masks shown in Fig. 36 are from the village of Reki'nniki. They differ from those from Paren by their large size, pointed chin, and in having ears. Besides this, one, Fig. 36, a, has a pendant like the Alutora masks, — in this case a bell, — and its cheeks are painted with ochre. Apparently Fig. 36, b, represents a man's mask; and Fig. 35, a, that of a woman.

Fig. 36 Masks from Reki'nniki (c, inner side).

85

JOCHLSON, THE KORYAK

Fig. 37

four masks

from Point Barrow,

which were

collected by Lieut. P. H. Ray's expedition,1

of which Mr.

Murdoch was a member, and are deposited in the

National Museum

in Washington.

Fig. 37. Eskimo Masks from Point Barrow (c, inner side).

There, as well as the other masks from Point Barrow, described by Mr. Murdoch, 2 differ little from the Koryak masks. They are somewhat better

1 The International Polar Expedition to Barrow, 1881-83. 2 Murdoch, p. 336

86

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

finished. All of them have openings for the eyes and mouth. The eyes are narrower than on the Koryak masks; and on two of them the outer corners of the eyes are somewhat raised. The face is less oval in form, and the nose is shorter: generally the forms of the Eskimo masks approach more closely the type which is called "Mongolian" than those of the Koryak. Fig. 37, c, represents the inner side of one of these masks, and shows that they are just as little hollowed out as those of Koryak make.

While in the village of Paren the wearing of masks is practised only during the first winter month after the new moon, in the settlements of northern

As soon as the approach of the herd is noticed,

the fire in the house is put out, and a

new fire is made outside the house with the sacred fire-board, and a pile

of wood

is ignited

with the new fire.

Burning brands are then laid

1 It is

worth while to note here, that, after the religious ceremonies which used to

take place in December,

the Aleutians broke and threw into the sea the

charms which they had used during the ceremonies, and the

masks worn by their men and women; and that every year they

made new charms and new masks (Dall, p. 139)

2 With the exception of the Alutora Reindeer Koryak (see p. 81)

87

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

upon boards, and thrown upon the approaching herd. According to explanations given by some of the Koryak, the herd is met with fire in the same manner as relatives and guests are welcomed; while, according to others, the fire signifies the source whence reindeer originated. According to the second version, The-One-on-High took the first reindeer out of the fire. After the fire has been taken out of the house, sacrificial reindeer are slaughtered as an offering to The-One-on-High, and the face of the guardian on the sacred fire-board is smeared with blood, that he may protect the herd from wolves during the winter. Well-grown fawns are selected for this purpose, their skins being used for winter garments.

The Fawn Festival. — In spring, about the month of April, when the fawning-period is over and the reindeer have lost their antlers, the fawn festival is celebrated. It is called ki'lvei. The fire in the house is put out, and a new one is started by means of the sacred fire-board. Then reindeer are slaughtered as a sacrifice to The-One-on-High. In the Palpal Mountains, both the Koryak and the Chukchee pile up the antlers of the killed reindeer. The other Reindeer Koryak do not observe this custom. . It seems probable that at an early period this custom was common to all Reindeer Koryak, though the Koryak of the Taigonos Peninsula deny ever having had it. However, the former existence of a custom is often disavowed as soon as it has ceased to be in vogue. Th( owner of the herd beats the drum in order to entertain the fawns. The does, so the official chief of the Taigonos Koryak told me, say, on hearing the drum, "Our master is amusing our fawns."

These two festivals — the end of the fawning period, and the return of the

herd in the fall — are the most important ones of the year. On such occasions, toothsome dishes are

prepared, and guests from the neighboring camps are entertained , but they are strictly

family festivals, nevertheless.

Other

Festivals. — The offering of

sacrifices constitutes the main feature of all other festivals. These are observed (1) when the sun marks the

approach of summer after the winter solstice — a sacrifice is then offered to

the sun; (2) in the month of March, when the

does commence to fawn — a sacrifice is offered to The-One-on-High; (3) in spring, when the grass

begins to sprout and the leaves appear on the

trees — a sacrifice is offered to the earth or to the master of the earth ; (4) when mosquitoes put in their appearance —

reindeer are then slain as an

offering to The-One-on-High, lest the mosquitoes scatter the herd.

Races.

— Reindeer races must also

be classed among the festivals of the Reindeer Koryak,

or they

are not

a mere

sport: they

are of a religious character, like the Creek games.

Races are festivals in honor of The-One-on- High. Dog-races

ad foot-races,

on the

other hand,

are not

regarded as religious

festivals. very owner of a large

herd arranges races once a year. They usually take ]

ace toward the close of winter. The owner of the camp invites

his guests

.

all the neighboring camps.

Before the beginning of

88

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

the races, a sacrifice is made to The-One-on-High.

Then the race begins; and the winner receives some tobacco, a knife, or some

other imported article, as a prize.

It happens sometimes that the host sacrifices the racing-reindeer which he has been riding. Before stabbing it, he

takes it around the house. In olden

times he wore a suit of armor on such occasions. I heard that even now rich people of the Palpal Mountains put on

armor1 when slaughtering sacrificial

reindeer during the race festival.

Festival of "Going around ivith the Drum."

— The Koryak of the Tai- gonos

Peninsula told me of a festival which they celebrate yearly after the winter solstice, and which is called

Ya'yai-kamle'lehryñin ("[with] drum around going"). Rich men invite all their neighbors to

this festival, offer a sacrifice to The-One-on-High, and slaughter many reindeer

for their guests. If there is

a shaman present, he goes all around the interior of the house, beating the drum, and driving away the kalau. He searches all

the people who are present in the

house, and, if he finds a kala's arrow (which is invisible to ordinary men) in the body of one of them, he pretends to

pull it out. In this manner he

protects them against disease and death. In the absence of a shaman, this act is performed by the host, or by a woman

versed in incantations.

Ceremonials Common to both Maritime and Reindeer Koryak. — The ceremonies performed after

hunting wild reindeer or other land-animals are the same among the Maritime and the Reindeer Koryak.

They are particularly

elaborate after successful bear or

wolf hunting. Unfortunately, I had no opportunity

to witness them personally; and the following descriptions are based on verbal information obtained from various

persons.

The Bear Festival. — The bear is equipped for the home journey, like the whale; and the

home-sending is called Ke'vñinacixtathi'yñin ("Bear-service").

|

|

When the dead bear is brought to the house, the women come out

Fig. 39 shows a wooden figure representing

the bear

during the festival.

It is fed in the same manner as the wooden whale during the whale festival. |

1 Suits of armor are preserved by many of the wealthy Reindeer people as heirlooms in remembrance of the ancient war times.

89

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

On the day when the bear

is equipped for the home journey, the Maritime Koryak prepare

puddings for it, travelling-provisions, just as has been described in connection with the

whale festival. They plait a grass bag, and put the puddings into it. The

Reindeer Koryak slaughter a reindeer for the bear, cook all the meat, and

pack it in a grass bag. The bear-skin is filled with grass, taken out and

carried around the house, following the course of the sun, and then sent

away in the direction of the rising sun. The fact that the bear is sent

toward morning dawn indicates that the Koryak consider the spirit of the bear as

benevolent. The stuffed bear and the bag are put on the platform of the storehouse; and after a few

days the skin is taken back to be tanned, and

the puddings are eaten.

The

Wolf Festival. — After having killed a wolf, the Maritime Koryak take off its

skin, together with the head, just as they proceed with the bear; then they place near the hearth a

pointed stick, and tie an arrow, called is'lhun or e/lgoi, to it,

or drive the arrow into the ground at its butt-end.1 One of the men puts on

the wolf's skin and walks around the hearth, while another member of the

family beats the drum. The wolf festival is called eslhõ'gicñin;

that is, "wolf-stick

festival."

The meaning of this ceremony is obscure. I have been unable to get any explanation from the Koryak

with reference to it. "Our forefathers did this way," is all

they say. I have found no direct indications of the existence of totemism among the

Koryak; but the wearing of the skin of the wolf and of the bear during

these festivals may be compared to certain features of totemistic festivals, in

which some members of the family or clan represent the totem by putting on its skin.

The wolf festival

differs from

the bear

festival in

the absence of the equipment for

the home

journey. The

reason is this, that the bear is sent home with much

ceremony, to

secure successful bear-hunting in the future, bear's meat being considered a delicacy, while the

festival serves at the same time to protect the people from the wrath of the slain animal and its

relatives. The

wolf, on

the other hand, does not serve as food, but is only a danger to the

traveller in

the desert.

He is dangerous, not

in his visible, animal state,

— for the northern wolves, as a rule, are

afraid of men, — but in his invisible, anthropomorphic form.

According to

the Koryak conception,

the wolf is a rich reindeer-owner and

the powerful master of the tundra.

A traveller who has lost his way

may stray into a settlement of wolves, and become their prey. The

wolves avenge

themselves particularly on those that hunt them. The Reindeer Koryak have still

more reason to fear wolves, since their herds are always exposed to their dangerous attacks.

According to the conception of

the Reindeer Koryak,

the wolf is a powerful

shaman, and he is regarded as an evil spirit hostile to

the reindeer, and roaming

all over the earth.

1 See p. 43. 2 Tale 84.

12—JESUP NORTH PACIFIC EXPED., VOL. VI.

90

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

tales he is not called by his usual name, E/gilñin, but Umya'ilhin ("broad-soled one") or Ña'iñinosa'n ("one who keeps himself outside").

After having killed a wolf, the Reindeer Koryak slaughter a reindeer, cut off its head, and put its body, with that of the killed wolf, on a platform raised on posts. The reindeer-head is placed so as to face eastward. It is a sacrifice to The-One-on-High, who is thus asked not to permit the wolf to attack the herd. Special food is prepared in the evening, and the wolf is fed. The night is spent without sleep, in beating the drum and dancing to entertain the wolf, lest his relatives come and take revenge. Beating the drum, and addressing themselves to the wolf, the people say, " Be well!" (Nime'leu gatva'ñvota!) and addressing The-One-on-High, they say, "Be good, do not make the wolf bad!"

Practices in Connection with Fox-Hunting. — When a captured fox is brought into the house, it is soothed like a child. While pulling off its skin, and cutting the joints of the legs, they say in a pitiful tone, "Eh, what a lean one!" to which some one replies for the fox, "I will soon send you a gray fox." A grass mat is put around the body like a coat. The male fox is given a little wooden knife, and the female a thimble and needle-case; then it is placed on the platform of the storehouse.

The sacrifices offered by the

Koryak to the supreme and other super- natural beings may be divided into two classes, —

bloody and bloodless ones. It

is remarkable, that, among the tribes of the northwestern part of North

America,

we find only bloodless offerings to the deities, consisting of food, ornaments, and other trifling

gifts.1 These sacrifices, however, play a secondary part. Among the Eskimo, the most

effective means of guarding against mis- fortune consists in the observance

of various taboos ; and a frank confession by the person who transgressed a

taboo 2 serves as the best

propitiatory measure. Among the Indians, purification, prayers, and incantations are

the most

effective means of gaining the good-will of the supernatural powers. Of course we find all these among the

Koryak also; but sacrifices play the most conspicuous part in their religious

life. It seems justifiable to assume that bloody sacrifices are connected

with the pastoral life of the Reindeer tribes, just as we find the same custom

among the cattle-raising tribes of Siberia generally, and among the Reindeer

peoples in the north of Siberia, as the Samoyed and Ostyak. It is probably not a mere accident

that in the myths recorded

by me, mostly

offerings of reindeer are mentioned; 3

but at present

1

See Boas, Baffin-Land Eskimo,

pp. 129,

146; Teit, pp. 344, 345; Boas,

Bella Coola Indians, p. 29.

2

Boas,

Baffin-Land Eskimo, p. 147.

3

A

dog-sacrifice is mentioned in but one tale,

No. 92. It should be

noted that the tales do not mention

at all sacrifices to evil spirits (kalau).

91

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

it is difficult to tell whether

the Koryak made offerings of dogs prior to the time when a part of them began to keep

reindeer-herds. The dog-raising Eskimo do not slaughter dogs as a sacrifice to

the spirits.1 Neither Steller nor Krasheninnikoff

mentions that the Kamchadal dog-breeders offered any sacrifices of dogs.

On the other hand, however, in North America, east of the Rocky Mountains, the Iroquois Indians

make sacrificial offerings of dogs; the Sioux also used to sacrifice dogs as well as make

bloodless offerings; 2 and the dog-raising Yukaghir3 of

northeastern Siberia, and the Gilyak4 of Saghalin and of the Amur River, killed dogs as

sacrifices to their deities or to their dead. The Gilyak, the Ainu, and some Tungus tribes of

the Amur region, make bloody sacrifices, killing

bears during their well-known bear festivals.5

If we now proceed to compare the nature of the bloody sacrifices of the Koryak

with those of the Siberian tribes, whose culture is of decidedly Asiatic type and shows no American

affiliation, and whose source of subsistence is cattle-raising, we shall find certain

marked differences.

Among the Buryat and the people of the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, bloody sacrifices are

still practised. Such sacrifices were formerly made in the country of the Urankhai (Soyot) and all

over lamaistic Mongolia; but, according to Potanin, 6

they have been abolished through the efforts of the lamas.

The custom of offering bloody sacrifices is even now in existence among the Yakut, in spite of the fact

that they were converted to Christianity from a hundred and fifty to

two hundred years ago. But while the Altai7 people, like the Koryak, offer

sacrifices to benevolent as well as to malevolent deities, to U'lgen- and Ye'rlik,

the Yakut slaughter horses and horned cattle to malevolent spirits (abasy')

only.8 They offer bloodless sacrifices exclusively, not only to the creative

forces (ayi'), but to the " masters" (icci') as well. They make

libations of kumiss to the head of the creative deities, Lord-Bright-Creator (Ayi'-Uru'ñ-Toyo'n);

while animals are merely consecrated to him, but not slaughtered. Consecrated

animals are not made use of. In olden times, rich Yakut

consecrated to

him entire

droves of horses,

which were driven

1 It is worthy of note here, that Turner (p. 196) says, «The tail of a living dog is often cut from its body in order that the fresh blood may be cast upon the ground to be seen by the spirit who has caused the harm, and thus he may be appeased." This seems to be a bloody offering.

2 Dorsey, pp. 426, 459, 522. «Mr. W. Hamilton," says Dorsey (p. 426), "who was a missionary to the Iowa and Sac Indians of Nebraska, saw dogs hung by their necks to trees, or to sticks planted in the ground, and he was told that these dogs were offerings."

3 See Jochelson, Yukaghir Materials, pp. 98, no, 122.

4 See Schrenck, III, pp. 765, 766.

5

Ibid.,

pp. 696-737.

6 Potanin, IV, p. 78.

8 Trostchanský (p. 105) gives the following reason why the Yakut offer bloody sacrihces exclusively to malevolent spirits (abasy'). The latter kill human beings in order to eat their souls (kut), w hich serve them as food; and the sacrifice serves as a substitute. The abasy' gets the kut of the animal instead of thet of a human being.

92

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

away eastward in the direction of the rising sun.1

The Buryat also offer

bloody sacrifices to

eastern Teñrii (evil deities) only.2 On

the contrary, the

Samoyed, like the Koryak, sacrifice reindeer

to the benevolent as well as to

the malevolent deities.3

The Koryak, as we shall further see, offer bloody sacrifices mainly to the Supreme Deity, to the sun, the "masters," the spirits of killed animals, to sacred rocks, in some cases to figures of kalak, and to the kalau (evil spirits). Formerly the Reindeer Koryak used to kill reindeer in honor of their dead also.

The conclusion may be drawn from the above, that, while among the Yakut and Buryat the cult of the evil principle has gained the upper hand over that of the creative forces, among the Koryak the cult of the benevolent spirit is more conspicuous.

Sacrifices are preventive, to avert a possible calamity or malady; propitia-tory, to remove a disaster which has already befallen ; and for giving thanks, in gratitude for benefits received. Thus sacrifices are offered not only at certain set times, but also on any and all occasions which may call for them. For instance, sacrifices are offered to secure a happy journey, that the hunt may prove successful, that a patient may be cured, that a storm may abate, that a famine may come to an end, or in gratitude for a happy consummation of a journey, for a recovery from disease, or for a successful hunt.

Not unfrequently a sacrifice is promised to the Supreme Deity conditionally, to be offered during a certain festival. As proof of such a promise, some kind of a bright-colored rag is sewed with sinew-thread to the ear of the promised animal; and the promised reindeer or dog is called ina'tiplin ("sewed or basted to").

Almost all sacrifices are made by the family or the individual. Only the sacrifice offered to the guardian of the settlement may be considered as a sacrifice for the inhabitants of the entire village.

Bloody Sacrifices. — While the Maritime Koryak kill only dogs as a sacrifice, the Reindeer Koryak slaughter reindeer as well. Dogs are killed by the Reindeer Koryak mainly as a sacrifice to the kalau. A reindeer offering is regarded as a more appropriate sacrifice. A white reindeer is looked upon as an offering particularly gratifying to the Supreme Being.

As a rule, when the Koryak offer sacrifices to the kalau, they do so with unconcealed reluctance. The sacrifice to the kalau is the price paid for preventing their attacks upon human beings. Some blood from the wounds of dogs or reindeer sacrificed to the Supreme Being is sprinkled on the ground

1

Among

both the Kamchadal and the Thompson Indians we find the custom of

consecrating to an idol

or to a spirit a certain portion of land, in which

they abide. The Kamchadal did not hunt, or gather berries,

around

the place

where the

sacred posts (see p. 38, Footnote 1)

were standing (Krasheninnikoff, II, p. 103);

also, among the Thompson Indians, "roots,

etc., growing near a haunted or mysterious lake should not be dug

or gathered" (Teit, p. 345).

2

Mikhailovsky.

Shamanism, p. 89.

3 Potanin, IV,

p. 697.

93

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

as an offering to the kala, with the words, "This blood is for thee, kala." Otherwise the kala might intercept the sacrifice, and prevent its reaching the Supreme Being, who resides in the sky. Figs. 40 and 41 are reproductions of sketches made by the Maritime Koryak Yulta, of Kamenskoye, and illustrate

these ideas. Fig. 40 shows a kala intercepting the sacrifice, and the

patient, who is treated by a

shaman, dying; while Fig. 41, a, represents the sacrifices reaching heaven,

and the patient being

cured. The

sacrifices offered to the Supreme Being are placed eastward, facing

the rising sun; while those offered

94

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

to the kala face toward the setting sun.1 The kalau come from this side. They sleep during the day, and after sunset go out hunting human beings. But at the same time I was told of kalau which come from the direction of Kamchatka, or from the east. Other kalau live in a subterranean kingdom. The blood from the wounds of animals sacrificed to the Supreme Being is sprinkled on the ground as an offering to them.

Sacrificial animals are killed by being stabbed in the heart with a spear. Dogs are killed in the following manner. One man holds a strap which is tied to the dog's neck; and another one stands back of the dog, holding it by a strap which encircles the hind part near the hind legs. The animal is thus held, unable to move. Frequently the dog does not suspect what is going to happen, wags its tail, and fawns upon the man in front, thinking that he is playing with it, or that he is about to hitch it to a sledge. A third man, who stands to the left of the dog, suddenly thrusts a spear into its heart (Plate vii, Fig. 2). It is considered a good sign if the dog is quiet before the blow, and does not resist. A long spear is therefore used, and not a knife, so that the animal may not be frightened. An unsuccessful blow is regarded as a bad sign. The men who are holding the dog pull the strap taut while the animal is writhing in convulsions, then they let it drop on its right side. In some places two men hold with their hands the dog that is to be killed; they lift it in the air, and a third one stabs it with a spear. An unsuccessful blow is regarded as a sign that the deity does not wish to accept the sacrifice: therefore the striking of the blow is intrusted to an experienced and skilful man. I recall, that, in the settlement of Paren, an excited young Koryak came running to me with a deep bite on his leg. He had held by- its head a dog that was to be sacrificed. The old man who was to kill the dog did not hit the heart at the first stroke; and before he was able to strike the second deadly blow, the dog managed to bite the leg of the Koryak who was holding its head. This sacrifice, which was offered on the occasion of the illness of a boy, was looked upon as not accepted by the deity; and another sacrifice was required, if the boy was to recover. The dogs killed as an offering to the Supreme Being are hung on a post, the upper pointed end

1 The creative deities of the Yakut are also supposed to reside in the east; and the chief of the upper evil spirits, Great-Lord (Ulu' Toyo'n), occupies the western part of the sky. Among the Altai people (Potanin, IV, P. 79) th skins of animals sacrificed to the benevolent deity (U'lgen') are placed head eastward; while the skins of animals sacrificed to the chief of the evil spirits (Ye'rlik) are placed head westward. The same is true among the Samoyed. When they stab a reindeer in sacrifice to the benevolent deity Numa, they put the killed animal head toward the east; but when the animal is sacrificed to the malevolent deity Av-Vesaka, head toward the west. After eating the meat of the sacrificed reindeer, they put the head on a post, turning it toward east or west according to the deity to whom the offering is made (Potanin, IV, p. 697). Among the Buryat, on the contrary, the benevolent Teñrii occupy the western part of the sky; and the evil Teîïrii the eastern (Agapitoff and Khangaloff, p. 4). It is interesting to note, in this connection, that the Bella Coola Indians place the evil in the west, and the good in the east. They regard the earth as an island swimming in the boundless ocean, and believe that when the mythical giant moves our earth westward, we have epidemics; when he moves it eastward, all sickness disappears (Boas, Bella Coola Indians, p. 37).

Jesup

North Pacific Expedition,

Vol.

VI.

Plate 1.

|

|

|

Fig. 1 Shaman's Jacket |

Fig. 2 Man's Dancing Jacket |

The Koryak.

Josup North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI Plate VIII

Fig. 2.

Undercround Houses, with Sacrihced Dogs.

The Koryak.

95

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK

of

which is thrust under the dog's lower jaw, so that its muzzle points up to the

sky, the ventral side

eastward. A

collar of sacrificial grass is put around the dog's neck.

The post with the dog hanging from it is driven into the ground or snow, not far from

the house; or a long pole with the sacrifice is placed close to the house, so

that the dog hangs over the roof (Plate viii,

Fig I). In

Kamens koye,

only the heads of the sacrifices are hung upon poles; while the carcass after the skin has been pulled off,

is thrown away. Since

the majority of dog-offerings are made in the interval between fall and spring,

the dogs slaughtered during that

time remain

hanging for a long time, usually

through the entire winter, until spring.

Then they are skinned, and the carcass is thrown away

The dogs sacrificed to the master

of the sea are left on the seashore, the muzzle facing the sea; those

offered to the mountains or rocks, called "grandfather"

(apa'pel), are placed on the summit or slope of a hill; and the sacrifice offered to

the kalau is left on the ground with the muzzle pointing westward. Sometimes the

offering intended for evil spirits is placed in the direction of the road

to be followed during a journey.

Dogs

sacrificed to the village guardian are sometimes hung up on the guardian itself (Plate IX, Fig. I).1

Reindeer sacrifices are also stabbed with a spear attached to a

long shaft, and not with a knife (as is usually done when reindeer are

slaughtered for food), in order to avoid frightening the reindeer, which is

required to stand still during the immolation. The reindeer designated as a