на

главную

| |

|

Shamanism |

47 |

|

General Remarks |

47 |

|

Professional Shamans |

47

|

|

Family

Shamanism |

54

|

| Incantations |

59

|

IV. — SHAMANISM AND INCANTATIONS.

Shamanism.

General Remarks. —

Shamanism may be defined as the art of influencing by the help of guardian spirits,

the course of events. Among the Koryak we may

distinguish professional shamanism and family shamanism. Professional shamans

are those who are inspired by special spirits. Their opportunities for displaying

their powers are not limited to a certain group of people. The more

powerful they are, the wider is the circle in which they can practise their

art. Family shamanism is connected with the domestic hearth, whose welfare

is under its care. The family shaman has charge of the celebration of

family festivals, rites, sacrificial ceremonies, of the use of their charms and

amulets, and of their incantations. Some women possess, besides the knowledge of

incantations which are a family secret, that of a, considerable number of other

incantations, which they make use of outside of the family circle for a consideration.

Professional

Shamans. — The professional

shaman is called eñe'ñalasn (that

is, a

man inspired by

spirits), from e'ñeñ

("shaman's spirit").1

Every shaman

has his

own guardian spirits, that help him in his struggle with the disease-inflicting

kalau, in his rivalry with other shamans, and also in attacks upon

his enemies. The shaman

spirits usually appear in the form of animals or

birds. The most common

guardian spirits are the wolf, the bear, the raven, the

sea-gull, and the

eagle. Nobody can

become a shaman of his own free will.

The spirits

enter into

any person they may choose, and force him to become

their servant. Those

that become shamans are usually nervous young men

subject to

hysterical fits,

by means

of which

the spirits express their demand

that the young man should consecrate himself to the service of shamanism. I

was told that people about to become shamans have fits of wild paroxysm alternating

with a condition of complete exhaustion.

They will lie motionless for

two or three days without partaking of food or drink. Finally they retire to

the wilderness, where

they spend their time enduring hunger and cold in order

to prepare

themselves for

their calling.

There the spirits appear to them

in visible form, endow them with power, and instruct them.

The second of

the two shamans

of whom I shall speak

below told me how the spirits of

the wolf, raven, bear, sea-gull,

and plover, appeared to him

in the desert, —

now in the form of men, now in that

of animals, — and commanded him to become a shaman,

or to die.

1 At present the Koryak also

term the

Christian God and the images

of the Orthodox Church

e'nen.

[47]

48

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

There

is no

doubt that professional shamanism

has developed from the ceremonials

of family shamanism.1

The latter form is more primitive, while the

functions of professional shamans somewhat resemble those of priests.

However, the

influence of contact

with a higher civilization has had a more disastrous effect

upon professional shamanism than upon that practised in the family.

There

was a time when the Koryak had all the different kinds of shamans

that

are still in existence among the Chukchee. The Koryak tell of miracles

performed

by shamans who have died recently, but at the present time there

are

very few professional shamans among them. I did not find a single shaman

in

the settlements of the Maritime Koryak along Penshina Bay. The old men

of

these settlements told me that many people had died among them during

|

the epidemic of measles

which

had ravaged these

regions before my

arrival,

because there were no shamans to drive away the

disease.3

The

Koryak shamans

have

no drums of their own:

they

use the drums belong-ing to the family in whose

house the shamanistic performance

takes place. It

seems

that they wear no

special

dress: at least, the

shamans

whom I had occasion

to observe wore

ordinary clothing. One

embroidered jacket (Plate 1,

Fig. 1) and head-band (Fig. 18) were sold to me for my collection as the garb

used by the Alutor shamans;

but

the jacket looks like an ordinary dancing-jacket used in the whale festival,

except

that it has some small tassels which have apparently been borrowed

from

Tungus shamans.

|

|

Fig. 18 (70/3386). Shaman's Head-Band. |

|

1 It is very strange that both

Steller and Krasheninnikoff, who spent several years in Kamchatka, assert

that the Kamchadal had no professional shamans, but that every one could

exercise that art, especially women

and Koe'kcuc (men dressed in women's clothes); that there was no special

shaman garb; that they used no

dram, but simply pronounced incantations, and practised divination (Krasheninnikôff,

III, p. 114; Steller,

p. 277), which description appears more like the family shamanism of the

present day. It is improbable that

the Kamchadal should form an exception among the rest of the Asiatic and

American tribes in having had no

professional shamans.

2

It is interesting to note that among the Yakut, a people with a more

developed primitive culture, the

embracing of Christian teaching has resulted in the decline of family

shamanism, which, according to Trostchansky

(p. 108), used to be practised among them, rather than that of special

shamanism. Professional shamans can

be found everywhere among the Yakut, even at the present time.

49

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

During

the entire period

of my sojourn among the Koryak I had opportunity

to see only two shamans.

Both were young men, and

neither enjoyed special

respect on the

part of his relatives.

Both were poor men who worked as

laborers for the rich members of

their tribe. One

of them was a Maritime Koryak

from Alutor.

He used

to come

to the village of Kamenskoye in company with a Koryak trader.

He was a bashful youth.

His features, though somewhat

wild, were flexible and pleasant, and his eyes were bright.

I asked him

to show

me proof

of his shamanistic

art. Unlike

other shamans, he consented

without waiting

to be

coaxed. The

people put out the oil-lamps in the

underground house in

which he stopped with his master.

Only a few coals

were glowing on the hearth, and

it was almost dark in the house.

On the

large platform which is

put up in the front part of the house as the seat and sleeping-place

for visitors,

and not far from where my wife and I were sitting, we

could just discern the shaman

in an ordinary

shaggy shirt of reindeer-skin, squatting

on the reindeer-skins that

covered the platform. His

face was

covered with a large oval

drum.

Suddenly

he commenced to beat the drum softly and to sing in a plaintive voice:

then the beating of the drum grew stronger and stronger; and his song

- in which could be heard sounds imitating the howling of the wolf, the

groaning of the cargoose, and the voices of other animals, his guardian spirits

— appeared to come, sometimes from the corner nearest to my seat, then

from the opposite end, then again from the middle of the house, and then

it seemed to proceed from the ceiling. He was a ventriloquist. Shamans versed

in this art are believed to possess particular power. His drum'also seemed

to sound, now over my head, now at my feet, now behind, now in front

of me. I could see nothing; but it seemed to me that the shaman was moving

around us, noiselessly stepping upon the platform with his fur shoes, then

retiring to some distance, then coming nearer, lightly jumping, and then squatting

down on his heels.

All

of a sudden the sound of the drum and the singing ceased. When the

women had relighted their lamps, he was lying, completely exhausted, on a

white reindeer-skin on which he had been sitting before the shamanistic performance

(Plate II. Fig. I). The concluding words of the shaman, which he pronounced

in a recitative, were uttered as though spoken by the spirit whom he

had summoned up, and who declared that the "disease" had left the

village, and would not return.

The

shaman's prediction suited me admirably, for one of the old Koryak had

forbidden his children to go into the house where I stopped to take measure-mgnts^jaying

that they would die if they allowed themselves to be

measyred. 1

1 It will be

interesting to quote here from the

work of Dr. Slunin (I, p. 378) on this

subject: "Up to this

time no

one has

taken any anthropological measurements

of the Koryak: and this

is impossible, for they are too ignorant and superstitious,

and they are exceedingly opposed to being measured.

They absolutely

refused to comply with our request

in this matter, despite

the hospitality we met in

their homes.

7—JESUP NORTH PACIFIC

EXPED., VOL.

VI.

50

JOCHELSON,

THE KORYAK.

He also tried to stir up the other Koryak against

me, pointing out to them

that

an epidemic of measles had broken out after the departure of Dr. Slunin's

expedition,

and that the same thing might take place after I left.

I

made an appointment with the shaman's master to have him call on

me,

together with the shaman, on the following day. I wished to take a record

in writing of the text of the

incantations which I had heard; but when I woke

up

in the morning, I was informed that

the shaman had left at daybreak.

I

saw another

shaman among

the Reindeer

Koryak of

the Taigonos Peninsula.

He had

been called

from a

distant camp

to treat

a syphilitic patient

who had large ulcers in his throat that made him unable to swallow. I

was not

present at

the treatment

of the patient, since the latter lived in another

camp, at

a distance of

several miles from us, and I

learned of the performance

of the rite only after it was over.

The Koryak asserted that the patient

was relieved

immediately after the shamanistic exercises, and that he drank

two cups of tea without any difficulty.

Among other things, the shaman ordered

the isolation

of the

patient from

his relatives,

lest the spirits that had

caused the

disease might pass to

others. A

separate tent was pitched next

to the

main tent for the

patient and his wife, who was

taking care of him.

I lived

in the

house of the patient's

brother, the official chief of the Taigonos

Koryak. At

my request he

sent reindeer

to bring the shaman. The

shaman arrived. His

appearance did not inspire much confidence.

In order to obtain a large remuneration, he

refused at first, under various

pretexts,

to perform his art. I asked him to "look at my road;" that is, to

divine

whether I should reach the end of my journey safely. The official chief

said

that this performance must take place in my own tent, and not in that

of

some one else; but the shaman declared that his spirits would not enter a

Russian

lodging, and that he would be in deadly peril if he should call up

spirits for a foreigner. Finally it was decided that the peril for the shaman

would

be eliminated by making his remuneration large enough to completely

satisfy

the spirits, I promised to give the shaman, not only a red flannel

shirt,

which he liked very much, but also a big Belgian knife. I had offered

him

first the choice of one of the two articles; but he declared that his spirits

liked

one as well as the other.

Another

difficulty arose over the drum. The chief himself found a way

out

of it by means of casuistry. He gave his own drum, saying that a family

drum

must not be taken into another Koryak's house, but that it was per-

missible

to take it into mine. The drum was brought into my tent by one

of

the three wives of the chief. It was in its case, because the drum must

not

be taken out of the house without its cover. A violation of this taboo

may

result in bringing on a blizzard.

During

the shamanistic exercises there were present, besides my wife

and

myself, the

chief, his wife who had brought the drum,

my cossack, and

Jesup

North Pacific Expedition, Vol. VI.

Plate II.

|

Fig. 2 |

Fig. 1 |

|

PERFORMING SHAMANS |

The

Koryak.

Jesup North Pacific

Expedition, Vol. VI.

Plate III.

SHAMANISTIC

PERFORMANCE

The

Koryak.

51

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

the

interpreter. The shaman had a position on the floor in a corner of the tent,

not far from the entrance (see Plate II, Fig. 2). He was sitting with his

legs crossed, and from time to time he would rise to his knees. He beat the

drum violently, and sang in a loud voice, summoning the spirits. As he explained

to me after the ceremony, his main guardian spirits (e'ñeñs) were

One-who -walks -around -the-Earth (No'taka'vya, one of the mythical names of

the bear), Broad-soled-One (Umya'ilhm,

one of the mythical names of the wolf), and the raven. The appearance of the spirits of these animals was accompanied

by imitations of sounds characteristic of their voices. Through their

mediation he appealed to The-One-on-High (Gi'cholasn) with the

following song, which was accompanied

by the beating of the drum: —

"Nime'leu

- neye'iten.

"(It

is) good that (he)

should arrive.

Nume'leñ

ho'mma nime'leu

ove'ka o'pta neye'itek."

Also

I

should well

myself also

reach home."

That

is, "Let

him reach

home safely,

and let me also reach home safely." Suddenly,

in the

midst of the wildest

singing and beating of the drum, he stopped,

and said

to me,

"The spirits

say that I

should cut myself with a knife.

You will not be afraid?"1 — "You may cut yourself,

I am not afraid," I

replied. "Give

me your knife, then.

I am

performing my incantations for you, so

1 have to cut myself with

your knife," said he.

To tell the truth, I

commenced to feel somewhat

uneasy; while my wife, who was sitting on the floor by

my side, and who was completely overwhelmed by the wild shrieks

and the sound of the drum,

entreated me not to give him

the knife. Until that

time I had heard different narratives about shamans cutting their abdomen, but

I had

never seen it done.

On the Palpal Mountains I was told that a woman shaman, who died quite recently, used to treat her patients by

opening the affected place, cutting out a piece of flesh, and

swallowing it, thus destroying the disease, together with the

spirit that had caused it.

It was said that the wound

she made

would heal up

immediately. Several

times I attended the exercises of a Tungus

shaman nicknamed Mashka, who

subsequently served me

as guide

on my

way from Gishiga to the

Kolyma. He

pretended that his guardians belonged to the Koryak spirits,

and demanded that he cut himself with his knife.

The wild fits of ecstasy which would possess him during his

performances frightened me.

In such cases he would

demand all those present

to give him a knife or a spear.

He was married to a Yukaghir woman from the Korkodon

River, whose

brother was

also a shaman.

She would always

search him before a performance, take away all his knives, and request all

those present not to give him any sharp instruments, for he had once cut himself nearly to death.

His spirits, being of Koryak origin, spoke out of him in the

Koryak language;

i. e., part

of the performance _was in_the_Koryak

1

Shamans, with the help of

the spirits, may cut and otherwise injure their bodies without suffering harm.

52

JOCHELSON,

THE KORYAK.

language. I asked him several times to dictate to

me what his spirits were

saving,

and he would invariably reply that he did not remember, that he forgot

ev'erything

after the seance was over, and that, besides, he did not understand

the

language of his spirits. At first I thought that he was deceiving me; but

I

had several opportunities of convincing myself that he really did not under-

stand

any Koryak. Evidently he had learned by heart Koryak incantations

which

he could pronounce only in a state of excitement.

To

return to our Koryak shaman. I took from its sheath my sharp

"Finnish"

travelling-knife, that looked like a dagger, and gave it to him. The

light

in the tent was put out; but the dim light of the arctic spring night (it

was

in April), which penetrated the canvas of the tent, was sufficient to allow

me

to follow the movements of the shaman. He took the knife, beat the

drum,

and sang, telling the spirits that he was ready to carry out their wishes.

After

a little while he put away the drum, and, emitting a rattling sound

from

his throat, he thrust the knife into his breast up to the hilt. I noticed,

however,

that after having cut his jacket, he turned the knife downward. He

drew

out the knife with the same rattling in his throat, and resumed beating

the

drum. Then he turned to me, and said that the spirits had secured for

me

a safe journey over the Koryak land, and predicted that the Sun-Chief

(Tiyk-e'yim)

— i. e., the Czar — would reward me for my labors.

Contrary

to my expectations, he returned the knife to me (I thought he

would

say that the knife with which he had cut himself must be left with him),

and

through the hole in his jacket he showed spots of blood on his body.

Of

course, these spots had been made before. However, this cannot be looked

upon as mere deception. Things visible and imaginary are confounded to such

an

extent in primitive consciousness, that the shaman himself may have thought

that

there was, invisible to others, a real gash in his body, as had been

demanded

by the spirits. The common Koryak, however, are sure that the

shaman

actually cuts himself, and that the

wound heals up immediately.

Shamans

that change their Sex. — Among the Koryak, only traditions

are

preserved of shamans who change their sex in obedience to the commands

of

spirits. I do not know of a single case of this so-called "transformation"

at

the present time. Among the Chukchee, however, even now shamans called

irka'-la'ul

may be found quite often. They are men clothed in woman's attire,

who

are believed to be transformed physically into women. The transformed

shamans

were believed to be the most powerful of all shamans. The con-

ception

of the change of sex arises from the idea, alluded to farther on, of

the

conformity between the nature of an object and its outer covering or garb.

Among

the Koryak they were called qava'u or qeve'u. In his chapter on

the

Koryak, Krasheninnikoff makes mention of the ke'yev, — i. e., men occu-

pying

the position of concubines,1 — and he compares them with the

Kamchadal

1 Krasheninnikoff, II, p.

222.

1 Krasheninnikoff, II, p.

222.

53

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

koe'kcuc,

as he

calls them;

i. e., men

transformed into women.

"Every koe'kcuc,"

says Krasheninnikoff,

"is regarded

as a magician and

interpreter of

dreams;" 1 but,

judging from

his confused description, it

may be inferred that

the most important feature of the institution of the koe'kcuc lay,

not in their

shamanistic power, but

in their position with regard to the satisfaction of

the unnatural inclinations of the Kamchadal.

The koe'kcuc wore women's clothes,

they did women's work, and were in the position of wives or concubines. They

did not enjoy respect: they held a social position similar to that of woman. They

could enter the house through the draught-channel, which corresponds to the

opening in the roof of the porch of the Koryak

underground house,- just like

all the women; while men would consider it a humiliation to do so.

The Koryak

told me the same with

reference to their qava'u. But, setting aside the

question of the perversion of the sexual instinct connected with this so-called "change

of sex," the interesting question remains,

Why is a shaman believed to

become more powerful when he is changed into a woman?3

The

father of Yulta, a Koryak from the village of Kamenskoye, who died

not long ago, and who had been a shaman, had worn women's clothes for

two years by order of the spirits; but, since he had been unable to attain complete

transformation, he implored his spirits to permit him to resume man's clothes.

His request was granted, but under the condition that he should put on

women's clothes during shamanistic ceremonies.4 As may be seen from Plate

II, Fig. I, the shaman

wears woman's striped trousers.

It

should be stated here that I did not learn of transformations of women shamans

into men among the Koryak of to-day, which transformations are known

among the Chukchee under the name qa'éikicheca ("a man-like [woman]").

5 We find, however, accounts of such

transformations in the tales; and the con-ception

of the change of sex is the same in both cases.

Women

shamans, and those transformed into women, are considered to be

very powerful. I

was told that a woman shaman on the Palpal Mountains

1 Krasheninnikoff, II, p. 114.

2

See p. 14, Footnote 4; and Steller, p. 212.

3

It is interesting to note that traces of the change of a shaman's sex into that

of a woman may be

found among many Siberian tribes. During shamanistic

exercises, Tungus and Yukaghir shamans put on, not

a man's, but a woman's, apron, with tassels. In the

absence of a shamanistic dress, or in cases of the so-called

"small" shamanism, the Yakut shaman will put

on a woman's jacket of foal-skins and a woman's white ermine

fur cap. 1 myself was once present at a shamanistic

ceremony of this kind in the Kolyma district. Shamans

part their hair in the middle, and braid it like women,

but wear it loose during the shamanistic performances.

Some shamans have two iron circles representing breasts

sewed to their aprons. The right side of a horse-skin

is considered to be tabooed for women, and shamans are

not permitted to lie on it. During the first three

days after

confinement, when Ayisi't, the deity of fecundity, is supposed to be near the

lying-in woman, access

to the house where she is confined is forbidden to men,

but not to shamans. Trostchansky (p. 123) thinks

that among the Yakut, who have two categories of

shamans, — the "white" ones representing creative forces,

and the "black" ones representing destructive forces, — the latter

have a tendency to become like women, for

the reason that they derive their origin

from women shamans.

4 Among

the Eskimo

"the servant

of the deity Sedna

is represented by a man dressed in a woman' s costume" (Boas,

Baffin-Land Eskimo, p. 140).

5 See Bogoras, Chukchee Materials,

p. xvii.

54

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

who was all covered with syphilitic ulcers, but

whom I had no opportunity

of

seeing, did not die because she was supported by her guardian spirits.

On the other hand, child-birth may result in a complete or temporary loss

of

shamanistic power. During the period of menstruation a woman is not

permitted to

touch a drum.

Eme'mqut's shamanistic power disappeared after the

mythical Triton had

bewitched

him, and caused him to give birth to a boy. His power was restored

to

him after his sister had killed the Triton's sister, by which deed the act of

giving birth was completely eliminated.1 Tale 113 also tells of the

transfor-

mation

of men into women. Illa' dressed himself like a woman and went to

his

neighbors. When River-Man (Veye'milasñ), the neighbor's son,

recognized

him,

Illa', in revenge, filled him with the continual desire to become a woman.

In

Tale 129

Kïlu"s brother became pregnant with twins. When he was

unable to give birth, his sister took out his entrails and put the entrails of a

mouse

in their place. After the children had been born, she replaced his

entrails.

Apparently the tranformation was not complete in this case.

Family Shamanism. The Drum. — In the chapter on guardians and

charms

I referred to the drum as a household guardian. In connection with

professional

shamanism I mentioned that the drum is closely connected with

shamanistic

performances, but not with the person of the shaman, as is the

case

among other Asiatic shamans. I shall point out here the part played

by

the drum in family shamanism.

The power of the drum lies in the sounds emitted

by it. On the one

hand,

the rhythm and change of pitch produced by skilful beating with the stick

evoke

an emotional excitement in primitive man, thus placing the drum in the

ranks

of a musical instrument. On the other hand, the sound of the drum,

just

like the human voice or song, is in itself considered as something living,

capable

of influencing the invisible spirits. The stick is the tongue of the

drum,

the Yukaghir say. As seen from Tale 9, The-Master-on-High himself,

in his creative activity, needs a drum. Big-Raven borrowed the drum from

him,

and gave it to men.

The

following song, which was sung while beating the drum by a Reindeer

Koryak woman of the Taigonos Peninsula, and

which may be regarded as a

prayer to the Creator (Tenanto'mwan),

to whom it was addressed, characterizes

the relation of the latter to the

acquiring of the drum by man.

Text.

| "Gi'ca |

ivi'hi' |

'ya'yai |

getei'kilin'

|

nime'leu |

mini'tvala

|

qoya'u

|

evi'yike |

I'miñ |

| "Thou

|

said, |

'drum |

make'

|

well |

(we)

shall live |

the reindeer |

not

dying |

also |

| yava'letin

|

kimi'ñu |

nime'leu." |

1

See

Tale 85.

55

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

Free Translation.

"You said

to us,

'Make a

drum.' Now let

us live

well, keep alive also the reindeer, and after our death grant good living

to our children."

In accordance with the

dual character of the drum, as a musical instrument and as a sacred object in the household, it is not

exclusively used for ritual purposes. Every member of the family may beat the

drum. It is beaten for amusement, for enchantment, for

propitiation of the gods, for summoning spirits, and also during family

and ceremonial festivals. In every family, however, there is one particular

member who becomes especially skilful in the art of beating the drum, and

who officiates at all the ceremonies in the series of festivals.

Women usually excel in the art of beating the drum (Plate III).

The Koryak drum (ya'yai) is somewhat oval in shape. The specimen represented in Fig.

19, front and back views of which are shown, is a typical

Fig.

19 (70/3184). Koryak Drum. a, Outer Side; b, Inner Side and Drum- Stick.

Koryak

drum in

size and

form. Its

long diameter is 73 cm.; the width of its

rim is 5 cm., and the length of the stick 45 cm.

The membrane covers the drum only on one

side. It is made

of reindeer-hide. The

Maritime Koryak sometimes

make the

drum-head of the skin of a dog or of that of a young spotted seal.

The drum-stick is made of a thick strip of whalebone, which is wider at the end that strikes the drum

than at the other end, and

is covered with

skin from

a wolf's tail. Inside

of the drum, at four points

in the rim, near its

edge, are tied double

cords made

of nettle-fibre, which meet at the lower part of the drum

and form the handle.

These cords are not arranged symmetrically, but all

towards one side of the drum. At

the top edge ot the rim are attached iron rattles. There is no doubt that the

custom of attaching

56

JOCHELSON,

THE KORYAK.

such

rattles to the drum has been borrowed from the Tungus.

Not all of the

Koryak

drums that I saw had iron

rattles. The

drum, before being used, is heated by the fire. Thus the hide is made

taut, and the sounds become clearer and

more sonorous.

|

Fig.

20 (70/8528). Yukaghir Drum and Drum-Stick

|

It is very interesting

to compare the

Koryak drum with other Asiatic drums which

I collected.

Fig. 20 represents a

Yukaghir

drum.1

Its longitudinal diameter is 88 cm.,

the width of the rim is 6.2 cm.,

and the length

of the stick is 42 cm.

The Yukaghir drum

is asymmetrical — somewhat

egg-shaped —

in form. It

is also covered with hide on one

side only.

Inside of the drum there is an

iron cross near

the centre, which serves as

a handle. The

ends of the cross are

tied

to the rim by means of straps.

Iron rattles

are attached at four places on the

inner side

of the rim. This

kind of drum is similar to

that of the Yakut.

This similarity may be

observed not only

in its shape,

the cross, and the iron rattles, but also in the

small protuberances on the outer

surface of the rim, which are espe-

cially characteristic of the Yakut

drum. They represent the horns

of the shaman's spirits. Judging

from what the old people among

the Yukaghir relate, in olden times

their drums had no metallic parts,

and were apparently like those of

the Koryak. The metallic parts

were borrowed from the Yakut.

The Yukaghir drum is, however,

larger in size than that of the Yakut,

and its rim is not so wide. The

stick is covered with skin of rein-

deer-legs. The drum-head is made

of reindeer-hide.

The

Yakut drum (Fig. 21) is |

Fig.

21 (70/9071). Yakut Drum and Drum-Stick

|

1 When in use,

the dram is held with

the broad end up, which is also the case with the Yakut drum

shown in the next figure.

57

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

covered

with hide of a young bull. Its longitudinal diameter is 53 cm.; the width

of the rim, 11 cm.; and the length of the stick, 32 cm. The wider part

of the stick is covered with cowhide. There are twelve protuberances representing

horns.1 The cross inside is attached to the rim by means of straps.

Little

bells and other metallic rattles are attached inside around the rim.

The

long diameter of the Tungus drum (Fig. 22) is 53 cm. In size and shape

it is almost like that of the Yakut; but its rim is narrower, in one specimen

only 7 cm. wide. The drum has no protuberances. The ends of the

cross are attached to the rim by means of a twisted iron wire. The iron rattles

are in the form

of rings strung upon wire bows attached to the rim.

In

comparing Asiatic with American drums, we observe that in most cases the

Eskimo drums are not large. The only large drums are

found among the tribes of the west coast of Hudson Bay.

They are either oval (but not asymmetrical) or round; the

rim is very narrow, like a hoop; and a wooden handle -is attached to the

rim," like that of a hand mirror (Fig. 23). Mr. J. Murdoch, in his paper

on the Point Barrow Eskimo,3

|

| Fig.

22 . Tungus Drum and

Drum-Stick.

Fig.

23. Eskimo Drum. Diameter, 87

cm.

|

says that such drums are used by the Eskimo from

Greenland to Siberia. The

drum

in Murdoch's illustration is somewhat oval in form (55 cm. by 47.5 cm.).

The

Chukchee use

the same

kind of

drum (Fig.

24) as

the Eskimo.

The Chukchee, as well as the

Eskimo, strike the lower part of the drum with

the stick.

1 Sieroszevskj (p. 635)

says that the protuberances are always in odd

numbers: 5,

7, and 11. 2

Potanin (IV, p.

678) tells that divinators

in China use

drams with handles. 3 Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology,

1887-88, p. 385.

8- JESUP

NORTH PACIFIC

EXPED., VOL.

VI.

58

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

The

Koryak drum approaches the Asiatic drum, but its handle is not of

metal:

it does not form a cross, and is not placed in the centre, but nearer

to

the lower edge. All asymmetrical drums are held (in the left hand) in

such

a way that the wider part of the oval points upward. Since the handle

of

the Koryak drum is not in the centre, it is held, when being beaten, in a slanting position, so that the stick strikes at

the

lower part of the membrane. Other Asiatic

drums

are mostly struck in the centre.

On the

American Continent,

proceeding

from the Eskimo southward,

we find among the

Indians small, round, broad-rimmed drums used for purposes of shamanism

as

well as in dancing-houses.

It

is interesting to note, that, according to Potanin's description,1

the

drums

of northwestern Mogolia and those of the natives of the Russian part

of

the Altai Mountains have not the egg-shaped form common to East Siberian

drums.

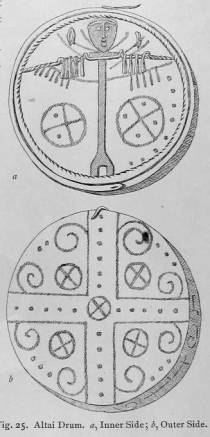

They are round, and not large in size. Fig. 25 represents both sides

of

an Altai drum, according to Mr. Potanin.2 Circles

and crosses representing

drums,

and other curved lines, are drawn upon the outer and inner sides of

the

membrane. Some Altai drums have drawings of animals,

like those on

1 Potanin, IV, pp. 44, 679.

2 Ibid., Plate XIII, Figs.

59

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

drums

of the North-American Indians. Instead of the cross, which serves as a

handle, we see on the Altai drum a vertical wooden stick, representing a human

figure, passing through the centre of the circle, and a horizontal iron chord

with rattles. The drum is held by the wooden stick, and not at the intersection

of the stick and the iron crossbar.1 In American drums, which have a

single head only, the straps attached to the hollow side, and crossing each other,

serve as a handle. These straps frequently form, not a cross, but a number

of radii. According to Dr. Finsch's description, 2 the drums of the Samoyed and of the Ob-Ostyak are,

like the Altai drums, round in shape, broad-rimmed, covered on one

side only, and have a diameter of from 30 cm. to

50 cm.

Drums

covered on both sides with hide, like those found among

the North-American

Indians, together with drums covered on but one side, are used

in Siberia only by the Buddhists (for instance, the Buryat), who use them in

their divine services. These drums are of a circular form, and have leather handles

attached to the

outer edge of the rim.

I

do not know whether the Koryak word for "drum" (ya'yai) has any other

meaning; but the Yukaghir word (yalgil) means "lake," that is, the

lake into which the shaman dives in order to descend into

the kingdom of shades. This is very much like the conception of the

Eskimo, the souls of whose shamans descend into the lower

world of the deity Sedna. The Yakut and Mongol

regard the drum as the shaman's horse, on which he ascends to the spirits

in the sky, or descends to those of

the lower world.

Incantations.

The

significance of family shamanism will become clearer by a discussion of

the festivals of the Koryak. It seems desirable, however, to treat first the magic

formulas used by them. In almost every family there is some woman, usually an

elderly one, who knows some magic formulas; but in many cases some

particular women become known as specialists in the practice of incantations, and

in this respect rival the powers of

professional shamans.

The

belief regarding magic formulas is, that the course of events may be influenced

by spoken words, and that the spirits frequently heed them; or that an

action related in the text of an incantation will be repeated, adapted to a given

case. In this way, diseases are treated, amulets and charms are consecrated, animals

that serve as food-supply are attracted,

and evil spirits are banished.

All incantations originate from the Creator (Tenanto'mwAn).

He bequeathed

1

Potanin (IV, p.

679) calls

attention to

the similarity of

the cruciform figures on

the drum to similar

figures on the clay cylinders discovered in

Italy, and considered to belong to the pre-Etruscan period ( Mortillet,

Le Signe de la

Croix avant

le Christianìsme: Paris, 1886,

pp. 80, 95, 96); but it does not seem to me thet the sign of the cross on the

drum-handle had

in itself any religious or

symbolical meaning.

2

Finsch, p. 550,

Plates 45, 47

60

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

them

to mankind to help them in their struggle with the

kalau. He and his

wife

Miti' appear as acting personages in the dramatical narrative which con-

stitutes

the contents of the magic formulas.

The incantations are passed from

generation

to generation;

but every

woman versed

in this art regards

her

formulas as a secret,

which, if divulged, would lose its power.

A magic formula

cannot serve

as an object of common use.

These women, when performing

an

incantation, pronounce

the formula,

and at

the same

time perform the

actions described in it.

This is done for a consideration.

I know of a woman

on the Taigonos Peninsula, whose husband was poor and a

good-for-nothing,

and who made a' living by incantations.

"The magic formulas are my reindeer,

they

feed me,"

she said to me.

A good incantation is worth several cakes

of pressed tea, or several packages of

tobacco, or a reindeer. When

a woman

sells an incantation, she must promise that she gives it up

entirely, and that

the buyer will become the only

possessor of its mysterious power.

At

first, during my stay among the Koryak, I was unable to record any

formulas

of incantations. To sell an incantation to a foreigner is considered

a sin. It was only after I had lived with them for several months that I was

able

to record the incantations given below. Formulas 1-3

were told me by

Navaqu't,

a Maritime woman from the village of Kuel; and 4 and 5, by

Ty'kken,

a Reindeer Koryak woman from a camp on the Topolovka River.

Before

dictating them to me, the women sent out of the house all the Koryak

except

my interpreter, lest they should make use of the formulas without

paying

for them.

1.

Incantation for the

Protection of a Lonely Traveller

against Evil Spirits.

Text.

| Tenanto'mwalan |

ala'itivoño'i: |

"Ki'miyñin," |

e'wan |

"i'cuca |

kala'iña |

naca'-` |

|

|

| (The)

Creator |

began to worry: |

"Son,"

|

says, |

"likely

|

by the kala |

carried |

|

|

| iciñin, |

ena'nneña |

yi'lqalan |

kala'iña |

naca'iciñin." |

Ele'enu |

tei'kenin |

e'lle |

aiño'ka. |

|

away

will

be, |

solitary |

sleeping-man |

by the kala |

carried away

will be."

|

In excre- ment

|

transformed

(him) |

not |

susceptible to smell(by the

kala). |

| tañ-i'lqañoi, |

teñ-ikye'vi. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Well

to sleep

began (son), |

well

woke up.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Free

Translation.

The

Creator began to worry, saying, "My son will probably be carried away by a

kala; he will be carried away by a kala while he is sleeping alone in the

wilderness." Therefore the Creator

transformed his son into excrement, for the kala does not like the smell

of it. Thus the son of the

Creator fell asleep well, and woke up without harm.

In

this incantation the belief is characteristic that the son

of the Creator

(that

is, the traveller), charmed

in this way, when preparing for the

night in

61

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

the wilderness,

is actually

turned by the Creator into

excrement, just as, in the Koryak 1

and Kamchadal 2

tales, Big-Raven's

excrement assumes the form of

a woman.

Something like

the same trend of

thought, though deviating somewhat

from it, is found in connection

with similar measures taken in other parts of Siberia for guarding

against evil spirits. Among

the natives of the Altai, if a person loses all his children, one after

another, his new-born child is given as ill-sounding

a name as possible:

for instance, It-koden ("dog's

buttocks"), thus trying to deceive the spirits which kidnap

the soul, making them believe that it is really a dog's buttocks.3

In a similar manner, wishing to convince the

spirits that the new-born child is a puppy, the Yakut call the child i't-ohoto'

; that is,

"dog's child."4

The Gilyak,

on their way home after hunting, call their

village Otx-mif

("excrement country"), in the belief that evil spirits will not follow them to such a bad village.5

2.

Incantation for charming an Amulet

for a Woman.

Text.

| Tenanto'mwan |

alai'tivoñoi |

e'voñoi: |

"Ñava'kketi

|

ci'nna |

qoc |

tye'ntyäsn?" |

|

|

| Creator |

think commenced |

say

commenced: |

"(For) daughter

|

what |

(I) |

shall

bring?" |

|

|

| Ye'nnin |

co'nnin |

ña'anen |

ci'llinin |

e'lle |

kama'kata |

ayo'ka |

Nenenke'vin |

yook. |

| Procured

|

brought |

that

|

hung |

not

|

(by) spirits |

visited. |

Caused stop |

visit. |

Free Translation.

The Creator considered, and said, "What shall I bring for my sick

daughter?" Then he procured an amulet,

brought it to his daughter, and placed it on her in order that the spirits

should not visit her. Thus the amulet 6

prevented the visit of spirits.

3. Incantation for the Treatment of Headache.

Text.

|

Tenanto'mwAnmak |

ena'n

|

cini'n |

lautita'lgm

|

nenatai'kmvoqen; |

ne'lqatqen |

|

|

(By the) Creator |

he

|

himself |

headache |

commences

to make; |

(he) goes |

|

| notai'te |

nenayo'qenat |

ñau'gisat. |

Quti'ninak |

aal |

cinca'tkinin |

qoli'ninak |

pe'kul |

| in the wilder- ness

|

overtakes |

two (all alone

with wife).

|

One |

axe |

holds |

one |

woman's

knife |

| cinca'tkinin. |

I'min |

ña'cit

|

inala'xtathenat |

nenanyai'tatqenat.

|

Nava' kikin |

le' ut |

|

| holds. |

All

|

those

|

(he) led away |

brought home. |

Daughter's

|

head |

|

| quti'ninak

|

a'ala |

nenaala'tkoñvoqen

|

quti'ninak |

vala'ta |

nenati'npuqen |

Miti' |

|

| one |

with

axe

|

knocks |

one

|

(with) knife |

thrusts. |

Miti' |

|

1 Tale

121.

2 Steller, p. 261.

3

Verbitsky, The Natives of the Altai, p. 86.

4

Trostchansky, p.55

5 L. J. Sternberg, Materials

for the Study of the Gilyak Language and Folk-Lore (Publication of the

Imperial Academy

of Sciences in St.

Petersburg, p. 31). In

press.

6 Any object given to wear

may serve as an amulet in this case, since it becomes a guardian

warding off

the visits of the kalau by virtue of the incantation.

62

JOCHELSON, THE

KORYAK.

|

eni'k |

cãke'tte |

nele'qin |

ni'uqin : |

"qawya'nvat |

ñava'kik." |

Ni'uqin

: |

"Ena'n |

cini'n |

| to

his |

sister |

goes

|

says: |

«Charm |

(my) daughter." |

Says: |

"He

|

himself |

| tashe'ñin |

tei'kinin |

Ena'n |

cini'n |

nenmeleve'nnin." |

|

|

|

|

| pain

|

made |

he |

himself |

let

cure." |

|

|

|

|

| Niyaiti'qen,

|

ni'uqin: |

"gina'n |

cini'n |

tashe'ñin |

getei'kili." |

|

|

|

| Comes

home, |

says:

|

"Thou

|

thyself |

pain

|

madest." |

|

|

|

| Ña'cit

|

ala'tkulat |

pane'nak |

galla'lenat.

|

Gichathicñe'ti |

nelle'qin.

|

Gicha'- |

|

|

| Those |

with axe

cutting |

to the old place |

carried off.

|

To country

of

dawn |

goes. |

In country |

|

|

| thicñik |

yaya'pel |

nenayo'qen |

Ña'visqat |

ña'nko |

va'tkin. |

Mi'lut |

ge'yillin. |

|

| of dawn |

little house |

reaches.

|

(A) woman

|

there

|

lives. |

Hare |

gave

(him). |

|

| Ganyai'tilin |

lawtika'lticñin |

Kai'ñan |

mi'lut,

|

le'vut |

kunme'levenin |

tethi'yñu |

|

|

| Brought home |

for

head-band. |

Cries

|

hare,

|

head

|

cures |

(with) seam |

|

|

| konnomaña'nen |

a'yikvan |

ne'lyi |

hekye'lin |

nime'leu.

|

Geme'leulin. |

|

|

|

| joins closer |

better

|

became

|

woke up |

better. |

Cured. |

|

|

|

Free

Translation.

The

Creator himself caused his daughter to have headache. He went to the wilderness,

and over-

took a couple, — a kala with his wife. The

former had an axe; the latter, a woman's knife. The

Creator took the couple and brought

them home. Then the kala commenced to knock with his

axe the head of Creator's daughter; and

the kala's wife began to hack the head of the girl with her

knife. Miti', the mother of the latter,

went to Creator's sister, and said, "Charm away my daughter's

headache."

Creator's sister answered, "The Creator himself caused the sickness:

let him cure it."

Then the Creator carried back to

their old place those who were knocking with the axe, and

cutting with the knife, the head of his daughter. . After that the

Creator went in the direction of

the dawn, and when he reached there, he came to a little house in which a woman

lived. The

woman gave him a hare. The Creator took it home, and of it made a

head-band for his daughter.

The hare cried out, and in that way cured the girl's head. The seams of

the injured skull joined

together. Each day she

woke up better, until she was entirely cured.

The

story contained in this incantation is as follows: Creator (or Big- Raven) went into the wilderness, met a kala with his wife, and took them

home.

The kala had an axe, and his wife had a woman's knife; and they

began

to cut the head of Big-Raven's daughter, owing to which she suffered

from headaches. Miti' went to Big-Raven's sister to ask her to work a charm

over

her daughter; but she was a woman shaman, and knew the cause of the

girl's

illness, and replied that her father himself had caused the illness, and

that

he should cure her himself. Miti' returned home, and said to her husband,

"You

yourself have caused the disease." Then he took the two kalau and

carried

them back to the wilderness.

In

order to cure his daughter's wounded head, he went toward sunrise.

There

he found a little house in which lived a woman. That woman, according

to

the explanation of the woman from whom this incantation was recorded,

was

the Sun herself. She gave Creator a hare to cure his daughter. He

took

the hare home, and tied it around his daughter's head. The hare cried,

and

cured her head with its crying. The wounds closed

up.

It may be remarked here

that the hare is an important amulet. It is

63

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

looked

upon as a strong animal, hostile to the kalau. In Tale 74 Eme'mqut kills

the kalau by throwing a hare's head into their house. During incantations, hare's

hair is plaited into the hair of the parts cut; and sometimes parts of the

hare — such as its nose, or a part of its ear — are attached to the charm-string.

Since the formula speaks of a hare whose cry is to effect the cure, and since in

reality the charm is made of a part or parts of a hare, it would

seem that these parts serve as

substitutes for the whole animal.

4.

Incantation for the Cure of

Swellings on the Arm.

Text.

| Tenanto'mwAnen |

Miti'in |

kimi'yñm |

e'wan: |

"Menganno'titkm."

|

"Miti', |

|

|

| Creator's

(and) |

Miti''s

|

son

|

says:

|

"Arm swells." |

"Miti'', |

|

|

| qo'yañ |

welv-i'san, |

walva-oca'mñin!"

|

Ganto'len |

a'ñqan

|

gagetacaña'ñvolen, |

|

|

| fetch |

raven's coat, |

raven's

staff!" |

Went out |

sea |

to look upon began, |

|

|

| galqa'llen |

anqatai'netin, |

vã'yuk |

gayo'len. |

Ya'xyax |

qolla |

milu'tpil |

koai'ñan. |

| went |

to sea-limit,

|

then |

reached.

|

Gull

|

other

|

little hare |

cry. |

| A'ñqan |

yawa'yte |

gapa'ñvolen. |

Esgina'n |

a'iñak |

ganapa'nñolen. |

"Tu'yi, |

ce'qäk |

| Sea |

great distance

|

(to) dry commenced. |

They

|

(by)

crying |

(to) dry

(the sea) commenced. |

"You

two,

|

what for |

| nayava'ñvotkinetik?"

|

E'wan: |

"Mu'yi |

tnu'tila |

tnutka'ltisño |

nayavañ'votkine'mok.

|

|

|

| used

are?" |

Say:

|

"We |

for

swollen, |

for

bandage on swelling |

used

are. |

|

|

| Mu'yi |

mitainanvotkme'mok, |

u'iña |

anno'tka!" |

E'wan: |

"Minyai'tatik!"

|

Nenayai'- |

|

| We two |

together cry, |

not

|

swells!" |

Says:

|

"Shall take you two

home!" |

Carried them |

|

| tatqenat |

ña'cit |

nenaya'vaqenat |

kimi'yñik |

tnutka'ltisño. |

NEnqä'uqin |

tïñu'tik. |

|

| two home

|

these

two |

uses

|

(on) son |

for bandage of

swelling. |

Stopped |

swelling. |

|

| Esgina'n

|

ai'ñak, |

tíno'tgisñin |

u'iña |

amai'ñatka. |

Am-aiña'nva

|

tíño'tgisñin |

|

| They |

when

cry, |

swelling |

not |

increases. |

All by means of crying |

swelling |

|

| nenmelewe'titkin.

|

Geme'leulin. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| improves. |

Recovered. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Free Translation.

Creator's and Miti"s son said, "My arm is swelling!" Then

Creator said to his wife, "Miti', fetch

my raven's coat and my raven's staff!" She brought them. Creator dressed

himself and went out to the sea, looked upon it, and

went to the limit of it. There he met a couple, — a gull and a little hare. Both were crying, and from their cry the tide became lower,

and the shore com-menced to dry. Creator

asked them, "For what are you both used?" They answered, "We are used for swollen men, — for a bandage on swelling.

When we both cry together, the swelling ceases." Then

Creator said, "I shall take you both home." Then he carried them both

home, and used both for a bandage on his son's swelling. From their cry, the

swelling ceased to increase. en, all by means of their

crying, the swelling improved, and Creator's son recovered.

When

the patient is a woman, the beginning of the incantation is : "Daughter of

the Creator and Miti'." The Creator asks Miti' for the coat and staff. The association in the text, of the idea that the crying of the gull

and hare causes

the tide to ebb and the swelling to go down, is interesting.

64

JOCHELSON, THE KORYAK.

recedes on account of the screaming of the gull

and of the hare ; and in the

same

manner the swelling is made to decrease by their screams. Of course,

on

the bandage or amulet, only parts of the hare or gull are used, such as

the

hare's hair or the beak of the gull; but these parts are substituted for

the whole animal.

5.

Incantation for Rheumatism in the Legs.

Text.

| Miti'in |

kimi'yñin |

nagi'tkataletqeñ. |

Vã'yuk |

Tenanto'mwanen |

krmi'yñin |

|

|

| Miti's |

son |

(with) legs ill. |

Then

|

Creator's |

son |

|

|

| nagitka'yan. |

"Ña'visqat,

|

qre'tgin |

welv-i'san,

|

walva-oca'mñin."

|

Vã'yuk |

|

|

| legs

(ill) |

"Wife, |

fetch |

raven's coat,

|

raven's staff." |

Then |

|

|

| ganto'len, |

ei'yen |

o'miñ |

ninencice'tqin.

|

Vã'yuk |

ci'ñei

|

es-gatgisñe'te, |

vã'yuk |

| ''went

out, |

sky |

always |

looked.

|

Then

|

flew

|

to sunrise, |

then |

| tín-u'pnäqu |

venviye'un. |

Es'ga'tgisñik |

vã'yuk |

gayo'len |

tín-u'pnäqum, |

gañvo'len |

|

| big

moimtain |

clearly

saw. |

On the sunrise side

|

then |

reached

|

big mountain, |

started |

|

| catapoge'ngik |

tin-u'pnäquk, |

vã'yuk |

gata'pyalen |

gisgo'lalqak. |

Ennë'n |

vä'aye'mkin |

|

| (to)

ascend

|

big mountain,

|

then

|

came up |

to

(the) very top. |

One

|

assembly

of grasses |

|

| nappa'tqen.

|

Vä'aykinin |

o'miñ |

yalña'gisne |

gayiki'sñilane, |

o'miñ |

cacopatkala'tke. |

|

| standing. |

Of grass

|

all

|

joints |

with mouths, |

all |

chewing. |

|

| "Tu'yu

|

ce'qäk |

nayavañvola'knatik

?" |

"Mu'yu |

gitkatalo'.

|

Mosginan |

ka'lau |

|

| "You

|

what for |

used are?"

|

"We

|

with leg-pain. |

We |

kalau |

|

| mitkono'mvonnan."

|

Ña'nen |

vä'a'yemkin

|

ninepyi'qin, |

nenanya'itatqen,

|

me'no |

|

|

| eat." |

That

|

assembly of grasses

|

pulled

out, |

carried home, |

where |

|

|

| ki'mi'yñinin

|

gitka'lgin |

nanena'ta

|

nenapnra'n-aqen. |

O'miñ

|

ka'lau |

vä'a'ya |

|

| son's |

leg

|

therewith

|

bound.

|

All

|

kalau |

(by

the) grass |

|

| ku'nñunenau,

|

o'miñ |

gitkalqa'tilau

|

ka'lau |

ku'nñunenau.

|

Vã'yuk |

geme'leulin, |

|

| eaten, |

all |

upon

legs coming |

kalau |

eaten.

|

Then |

recovered, |

|

| gaenqäeu'lin |

gitkata'lik |

ge'mge-kye'vik |

ayi'kvan.

|

Geme'leulin. |

|

|

|

| ceased |

leg suffer |

at every awakening |

anew. |

Recovered. |

|

|

|

Free

Translation.

Miti"s

and Creator's son had pains in his legs. Then Creator said to Miti', "Wife,

fetch my

raven coat and raven staff." Then Creator went out and always looked

up at the sky. Then

he flew in the direction of the dawn. Soon he caught sight of a big

mountain on the side of

sunrise. He reached that mountain, started to ascend it, and finally went

to the very top of it.

There he found an assembly of Grasses. All their joints had mouths that

were always chewing.

"For what are you used?" asked, then, Creator. "Our legs

pain us," answered the Grasses; "and

we eat the kalau that cause the pain."

Creator

drew that assembly of Grasses out, carried them home, and bound his son's legs

with

them. The Grasses ate all kalau that came upon the legs and caused the

pain. Then Creator's

son ceased to suffer with his legs, at every awakening he felt better,

and finally recovered.

It

may be remarked, in connection with this formula, that the grass

mentioned

is a species of Equisetacece, the joints of which are regarded as mouths

that

eat kalau. Grass

charmed in this manner is tied around the affected part.